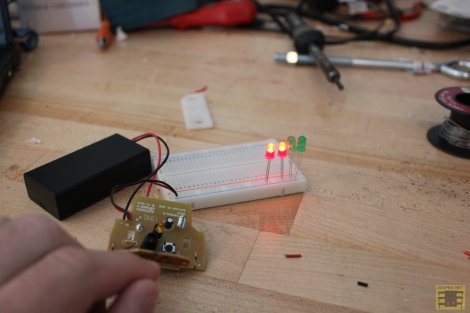

We’ve seen air fresheners used for many hacks here at hackaday. This one is a bit different as it uses the PIR sensor assembly to turn on LEDs in sequence, rather than reversing a motor. Generally, the motor would be reversed by the fact that this assembly is reversing the voltage on a motor (see [H Bridge] on Wikipedia), but instead it turns on one set of LEDs and then the other.

This works because a diode (the “D” in LED) only allows current to flow one way. The LEDs are reversed with respect to the voltage source, making them come on in sequence. An Arduino or other microprocessor could of course be used to accomplish the same thing (see this [HAD] post about harvesting the PIR sensor only). However, if you had $10 or less to start your hardware hacking career, this is yet another way an air freshener can be hacked up to do your bidding.

Be sure to see the video of this simple hack after the break, used to “LED-ify” a Star Wars AT-ST painting. If you’re interested in using the gears and motor of an air fresher as well, why not check out this post on remotely triggering a camera with the internals from a time-based model? Continue reading “Another Automatic Air Freshener Use”