[Matthiew] needed to create a system that would allow a computer to read braille. An electromechanical system would be annoying to develop and would require many hardware iterations as the system [Matthew] is developing evolves. Instead, he came up with a much better solution using a webcam and OpenCV that still gets 100% accuracy.

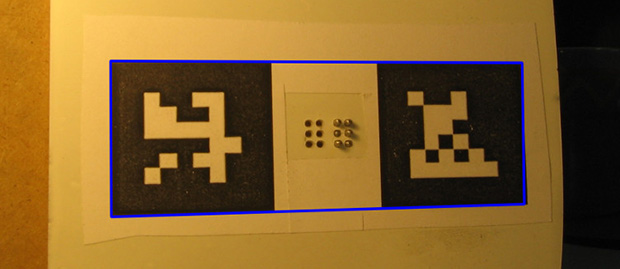

Instead of using a camera to look for raised or lowered pins in this mechanical braille display, [Matthiew] is using OpenCV to detect the shadows. This requires calibrating the camera to the correct angle, or in OpenCV terms, pose.

After looking at the OpenCV tutorials, [Matthiew] found a demo that undistorts an image of a chess board. Using this same technique, he used fiducials from the ARTag project to correctly calibrate an image of his mechanical braille pins.

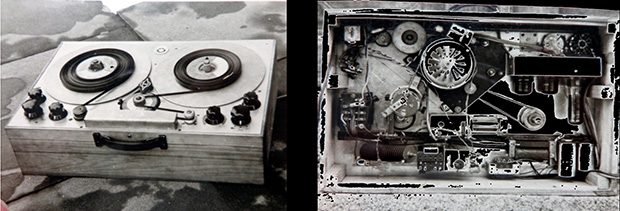

As for why [Matthiew] went through all the trouble to get a computer to read braille – something that doesn’t make a whole lot of sense if you think about it – he’s building a braille eBook reader, something that just screams awesome mechanical design. We’d be interested in seeing some more info on that project as well.