Phlebotomy is a fun word, and the fine art of finding veins. While the skill of putting needles in arms is honed by nurses and physicians over the course of decades, there are, of course, technological solutions to finding veins. One of the more impressive medical devices that does this uses near-infrared imaging — basically looking under the skin with almost visible light. These devices cost a fortune.

One project in the Hackaday Prize is looking to change that. It’s a near-infrared vein finder. Instead of the thousands of dollars professional unit costs, this one can be built for under one hundred bucks.

As far as this build goes, veins are illuminated via IR light at about 950nm. The backscatter of this light is captured via a Raspberry Pi NoIR camera, with regular old photography film blocking visible light. From there, it’s just a simple matter of image processing and hitting enhance several times until veins appear on a display.

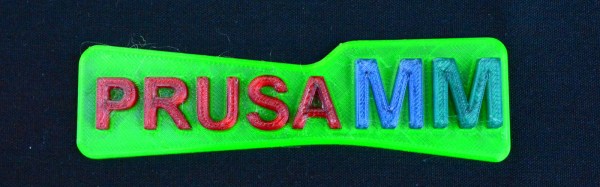

The team behind this project has already developed a mobile version of the device, complete with 3D printed parts. It’s a handy device and a great entry for the Hackaday Prize.