Mars ain’t the kind of place to raise a kid. In fact, it’s cold as hell. There’s no one there to raise them if you did, or is there? Is there life on Mars? That’s the question NASA has been trying to answer for the last forty years, and with the new Mars rover, we might get closer to an answer. For this week’s Hack Chat, we’re going to be talking with the people responsible for some interesting instruments flying on the Mars 2020 rover.

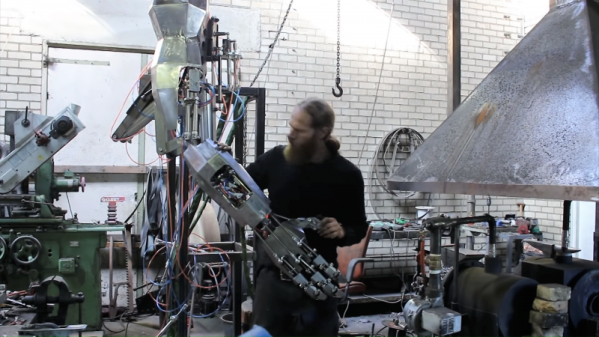

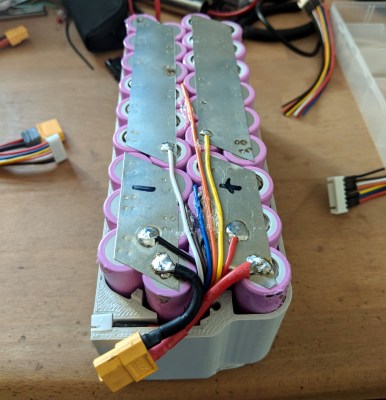

Our guest for this week’s Hack Chat will be [Matteo Borri], an Italian engineer who’s been living in the US for the better part of a decade now. He’s had various projects ranging from robotics — including a BattleBot — AI, and aerospace. [Matteo] is also one of the engineers behind the Vampire Charger, a winner in the Power Harvesting Module Challenge in this year’s Hackaday Prize.

Our guest for this week’s Hack Chat will be [Matteo Borri], an Italian engineer who’s been living in the US for the better part of a decade now. He’s had various projects ranging from robotics — including a BattleBot — AI, and aerospace. [Matteo] is also one of the engineers behind the Vampire Charger, a winner in the Power Harvesting Module Challenge in this year’s Hackaday Prize.

Right now, [Matteo] is working on an interesting project that’s going to fly on the next Mars rover. He’s developed a chlorophyll spectroscope for NASA and the Mars Society. This week, [Matteo] is going to share the details of how this device works and how it was developed.

During this Hack Chat, we’re going to be discussing various technology that’s going into the search for life on Mars and elsewhere in the galaxy such as:

- Chlorophyll detection

- Mars Rovers

- Various other hardware hacks

You are, of course, encouraged to add your own questions to the discussion. You can do that by leaving a comment on the Hacking with Fire event page and we’ll put that in the queue for the Hack Chat discussion.

Our Hack Chats are live community events on the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Friday, October 5th, at noon, Pacific time. We have some amazing time conversion technology.

Click that speech bubble to the right, and you’ll be taken directly to the Hack Chat group on Hackaday.io.

You don’t have to wait until Friday; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.