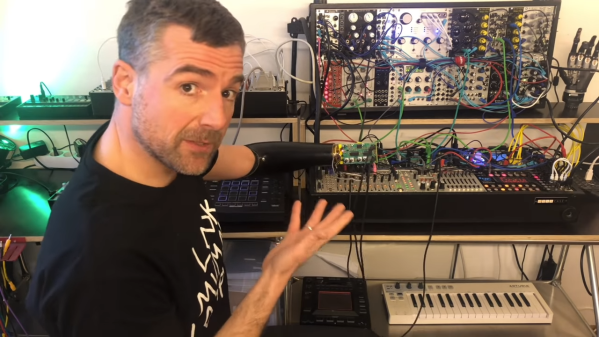

As amazing as prosthetic limbs have become, and as life-changing as they can be for the wearer, they’re still far from perfect. Prosthetic hands, for instance, often lack the precise control needed for fine tasks. That’s a problem for [Bertolt Meyer], an electronic musician with a passion for synthesizers with tiny knobs, a problem he solved by hacking his prosthetic arm to control synthesizers with his mind. (Video, embedded below.)

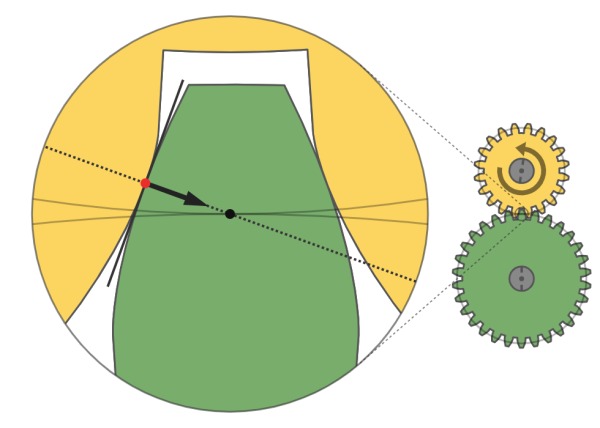

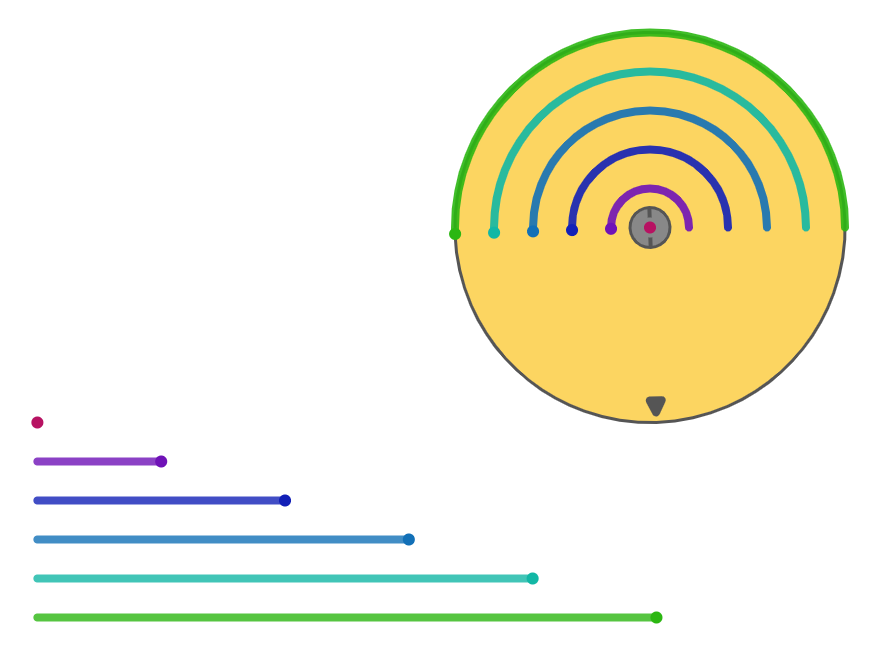

If that sounds overwrought, it’s not; [Bertolt]’s lower arm prosthesis is electromyographically (EMG) controlled through electrodes placed on the skin of his residual limb. In normal use, he can control the servos inside the hand simply by thinking about moving muscles. After experimenting a bit with an old hand, he discovered that the amplifiers in the prosthesis could produce a proportional control signal based on his inputs, and with a little help from synthesizer manufacturer KOMA Electronik, he came up with a circuit that can replace his hand and generate multiple control voltage channels. Plugged into any of the CV jacks on his Eurorack modular synths, he now has direct mind control of his music.

We have to say this is a pretty slick hack, and hats off to [Bertolt] for being willing to do the experiments and for enlisting the right expertise to get the job done. Interested in the potential for EMG control? Of course there’s a dev board for that, and [Bil Herd]’s EMG signal processing primer should prove helpful as well.

Continue reading “Hacked Prosthesis Leads To Mind-Controlled Electronic Music”