We are entering a new era of radio technology. A new approach to building radios has made devices like multi-band cell phones and the ubiquitous USB TV receivers that seamlessly flit from frequency to frequency possible. That technology is Software Defined Radio, or SDR.

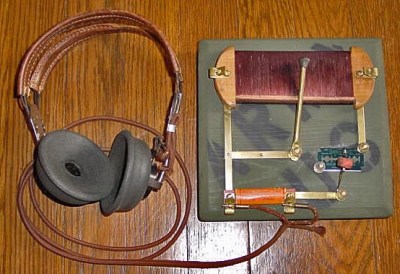

A idealized radio involves a series of stages. Firstly, an antenna receives the radio signal, converting it into an electrical signal. This signal is fed into a tuned resonator which is tuned to a particular frequency. This amplifies the desired signal, which is then sent to a demodulator, a device which extracts the required information from the carrier signal. In a simple radio, this would be the audio signal that was encoded by the transmitter. Finally, this signal is output, usually to a speaker or headphones.

That’s how your basic crystal radio works: more sophisticated radios will add features like filters that remove unwanted frequencies or additional stages that will process the signal to create the output that you want. In an FM radio, for example, you would have a stage after the demodulator that detects if the signal is a stereo one, and separates the two stereo signals if so.

To change the frequency that this radio receives, you have to change the frequency that the resonator is tuned to. That could mean moving a wire on a crystal, or turning a knob that controls a variable capacitor, but there has to be a physical change in the circuit. The same is true of the additional mixing stages that refine the signal. These circuits may be embedded deeply in the guts of the radio, but they are still there. This is the limitation with normal receivers: the radio can’t receive a signal that is outside the range that the resonator circuit can tune to, or change the way it is demodulated and processed. If you want to receive multiple frequency bands or different types of signals, you need to have separate pathways for each band or type of signal, physically switching the signal between them. That’s why you have physical AM/FM switches on radios: they switch the signal from an AM radio processing path to an FM one.

Software Defined Radios remove that requirement. In these, the resonator and demodulator parts of the radio are replaced by computerized circuits, such as analog to digital converters (ADCs) and algorithms that extract the signal from the stream of data that the ADCs capture. They can change frequencies by simply changing the algorithm to look for another frequency: there is no need for a physical change in the circuit itself. So, an SDR radio can be tuned to any frequency that the ADC is capable of sampling: it is not restricted by the range that a resonator can tune to. Similarly, the demodulator that extracts the final signal you want can be updated by changing the algorithm, changing the way the signal is processed before it is output.

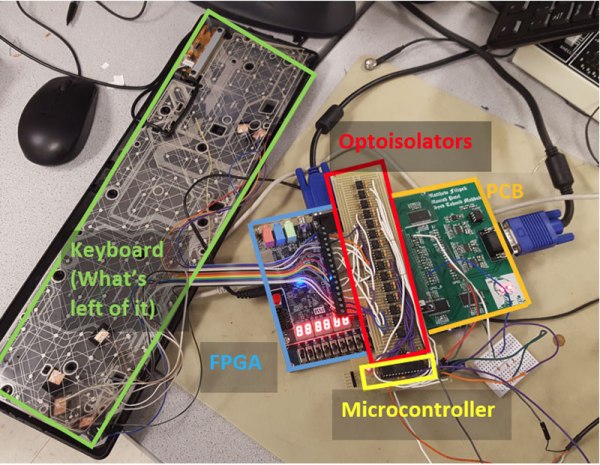

This idea was first developed in the 1970s, but it didn’t really become practical until the 1990s, when the development of flexible field-programmable gate array (FPGA) chips meant that there was enough processing power available to create single chip SDR devices. Once programmed, an FPGA has no problem handing the complex tasks of sampling, demodulating and processing in a single device.

Most modern SDRs don’t just use a single chip, though. Rather than directly converting the signal to digital, they use an analog front end that receives the raw signal, filters it and converts it down to a fixed frequency (called the intermediate frequency, or IF) that the ADCs in the FPGA can more easily digitize. This makes it cheaper to build: by converting the frequency of the signal to this intermediate frequency, you can use a simpler FPGA and a cheaper ADC, because they don’t have to directly convert the maximum frequency you want to receive, only the IF. As long as the front end can convert a band of signals down to an intermediate frequency that the FPGA can digitize, the SDR can work with it.

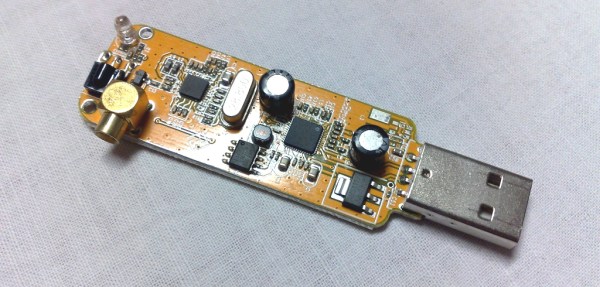

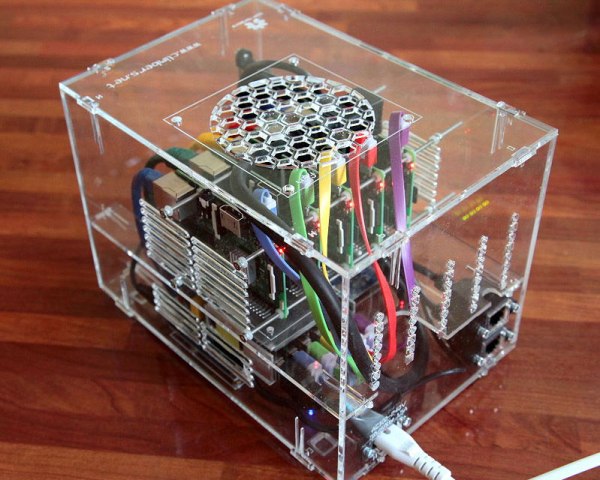

This flexibility means that SDR devices can handle a huge range of signals at relatively low cost. The $420 BladeRF, for instance, can receive and transmit signals from 300 MHz to 3.8 GHz at the same time, while the $300 HackRF One can work with signals from 1 MHz up to an incredible 6 GHz. The ability of the BladeRF to both receive and transmit means that you can use it to build your own GSM phone network, while the low cost of the HackRF One makes it a favorite of radio hackers who want to do things like make portable radio analyzers. Mass produced models are even cheaper: by hacking a $20 USB TV receiver that contains an SDR, you can get a radio that can, with a suitable antenna, do things like track airplanes or receive satellite weather images. And all of this is possible because of the idea of Software Defined Radio.

[Main image source: DVB dongle by Dsimic on Wikipeda CC-BY-SA]