When a consumer electronics device is sold in the US, especially if it has a wireless aspect, it must be tested for compliance with FCC regulations and the test results filed with the FCC (see preparing your product for FCC testing). These documents are then made available online for all to see in the Office of Engineering and Technology (OET) Laboratory Equipment Authorization System (EAS). In fact, it’s this publishing in this and other FCC databases that has led to many leaks about new product releases, some of which we’ve covered, and others we’ve been privileged enough to know about before the filings but whose breaking was forced when the documents were filed, like the Raspberry Pi 3. It turns out that there are a lot of useful things that can be accomplished by poring over FCC filings, and we’ll explore some of them.

Author: Bob Baddeley94 Articles

Preparing Your Product For The FCC

At some point you’ve decided that you’re going to sell your wireless product (or any product with a clock that operates above 8kHz) in the United States. Good luck! You’re going to have to go through the FCC to get listed on the FCC OET EAS (Office of Engineering and Technology, Equipment Authorization System). Well… maybe.

As with everything FCC related, it’s very complicated, there are TLAs and confusing terms everywhere, and it will take you a lot longer than you’d like to figure out what it means for you. Whether you suffer through this, breeze by without a hitch, or never plan to subject yourself to this process, the FCC dance is an entertaining story so let’s dive in!

Books You Should Read: Poorly Made In China

This book is scary, and honestly I can’t decide if I should recommend it or not. It’s not a guide, it doesn’t offer solutions, and it’s full of so many cautionary tales and descriptions of tricks and scams that you will wonder how any business gets done in China at all. If you are looking for a reason not to manufacture in China, then this is the book for you.

The author is not involved in the electronics industry. Most of the book describes a single customer in the personal products field (soap, shampoo, lotions, creams, etc.). He does describe other industries, and says that in general most factories in any industry will try the same tricks, and confirms this with experiences from other similar people in his position as local intermediary for foreign importers.

Continue reading “Books You Should Read: Poorly Made In China”

Hackaday Dictionary: Mux/Demux

In this issue of Hackaday Dictionary, we cover the multiplexer and demultiplexer (also called mux and demux). They are essentially opposites but they work on the same principle. There are three parts: the input, the output, and the selector.

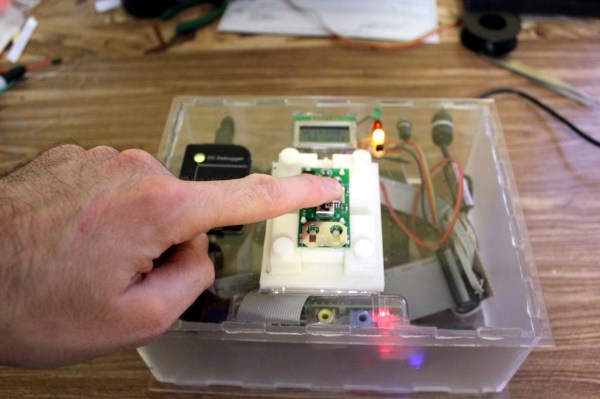

Tools Of The Trade – Test And Programming

In our final installment of Tools of the Trade (with respect to circuit board assembly), we’ll look at how the circuit board is tested and programmed. At this point in the process, the board has been fully assembled with both through hole and surface mount components, and it needs to be verified before shipping or putting it inside an enclosure. We may have already handled some of the verification step in an earlier episode on inspection of the board, but this step is testing the final PCB. Depending on scale, budget, and complexity, there are all kinds of ways to skin this cat.

Continue reading “Tools Of The Trade – Test And Programming”

Hackaday Dictionary: Mils And Inches And Meters (oh My)

Measuring length is a pain, and it’s all the fault of Imperial measurements. Certain industries have standardized around either Imperial or metric, which means that working on projects across multiple industries generally leads to at least one conversion. For everyone outside the last bastion of Imperial units, here’s a primer on how we do it in crazy-land.

Definitions

The basic unit of length measurement in Imperial units is the inch. twelve inches make up one foot, three feet make up one yard, and 5,280 feet (or 1,760 yards) make up a mile. Easy to remember, right?

Ironically, an inch is defined in metric as 25.4 millimeters. You can do the rest of the math for exact lengths, but in general, three feet is just shy of a meter, and a mile is about a kilometer and a half. Generally in Imperial you’ll see lots of mixed units, like a person’s height is 6’2″ (that’s shorthand for six feet, two inches.) But it’s not consistent, it’s English; the only consistency is that it’s always breaking its own rules. You wouldn’t say three yards, two feet, and six inches; you’d say 11 1/2 feet. If it was three yards, one foot, and six inches, though, you’d say 3 1/2 yards. There’s no good rule for this other than try to use nice fractions as often as you can.

Users of Imperial units love fractions, especially when it comes to parts of an inch or mile. You’ll frequently find drill bits in fractions of an inch, which can be extremely frustrating when you are trying to do math in your head and figure out if a 17/64″ bit is bigger than a 1/4″ bit (hint, yes, it’s 1/64″ bigger).

If it wasn’t hard enough already, there came the thousandth of an inch. As the machine age was getting better and better, and parts were getting smaller and more precise, there came a need for more accurate measurements than 1/64 inch. Development of appropriate tools for measuring such fine resolution was critical as well. You can call a 1/8″ bit a .125″ bit, and that means 125 thousandths of an inch. People didn’t like to wrap their mouths around that whole word, though, so it was reduced to “thou.” Others used the latin root for thousand, “mil.” To summarize, a mil is the equivalent of a thou, which is one thousandth of an inch. It should not be confused with a millimeter. It takes about 40 mils to make 1 millimeter. Also, the plural of mil is mils, and the plural of thou is thou.

Tools

![Outside calipers for measuring the outer dimensionBy Glenn McKechnie (Own work) [GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/outsidecalipers.jpg?w=400)

Also, while slightly off topic, if you haven’t seen this video on getting the most out of your tape measure, it’s well worth a few minutes.

Uses

Every industry has picked a different convention. Plastic sheets are usually measured in mils for thin stuff and millimeters or fractions of an inch for anything greater than 1/32″. Circuit boards combine units in every way imaginable, sometimes combining mils for trace width and metric for board dimensions, with the thickness of the copper expressed in ounces. (That’s not even a unit of length! It represents the amount of copper in one square foot of area and 1 oz is equivalent to 1.4mil.) Most of the time products designed outside of the U.S. are in metric units, while U.S. products are designed in either. When combining different industries, though, the difference in standards gets really annoying. For example, order 1/8″ plexiglass, and you may get 3mm plexiglass instead. Sure the difference is only .175mm (7 thou), but that difference can cause big problems for pieces that are press fit or when making finger joints on boxes, so it’s important that when sourcing components, you not only verify the unit, but if it’s a normal unit for that industry and it’s not just being rounded.

Often you can tell with what primary unit a product is designed with only a few measurements of a caliper. Find a dimension and see if it’s a nice round number in metric. If it’s not, switch it to imperial, and watch how quickly it snaps to a nice number.

Moving forward

Use metric if you can. The vast majority of the world does it. When you are sending designs overseas for production they will convert to metric (though they are used to working in both). It does take time to get used to it (especially when you are dealing with thou/mils), but your temporary discomfort will turn to relief when your design doesn’t crash into the Mars (or more realistically when you don’t have to pull out the Dremel and blade to get your parts to fit together).

Firearm Tech – Are Smart Guns Even Realistic?

At frustratingly regular intervals, the debate around gun control crops up, and every time there is a discussion about smart guns. The general idea is to have a gun that will not fire unless authenticated and authorized. There’s usually a story about a young person who invents a smart controller and another company that is struggling because they just can’t get “Big Guns” to buy into the idea. We aren’t going to focus on the politics; we’re going to look at whether the technology is realistic, and why a lot of the news stories about new tech never pan out.

Let’s start with an example of modern technology creeping into established machines: the car. These are giant hunks of metal with nearly constant explosions, controlled by sophisticated electronics that are getting smarter and more connected every day. Industry is adopting it with alacrity, and the vehicles are getting more efficient and powerful because of it. So why can’t firearms?

Continue reading “Firearm Tech – Are Smart Guns Even Realistic?”