The Before Times were full of fancy logic analyzers. Connect the leads on these analyzers to a system, find that super special ROM cartridge, and you could look at the bus of a computer system in real time. We’ve come a long way since then. Now we have fast, cheap bits of hardware that can look at multiple inputs simultaneously, and there are Open Source solutions for displaying and interpreting the ones and zeros on a data bus. [hoglet] has built a very clever 6502 protocol decoder using Sigrok and a cheap 16-channel logic analyzer.

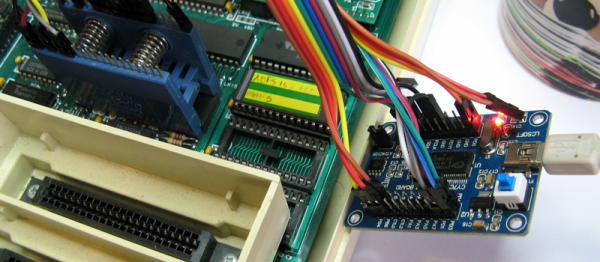

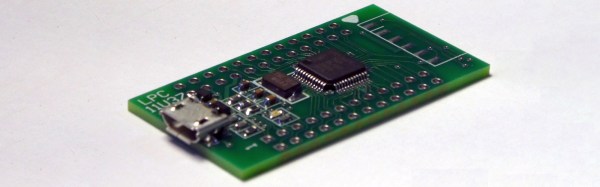

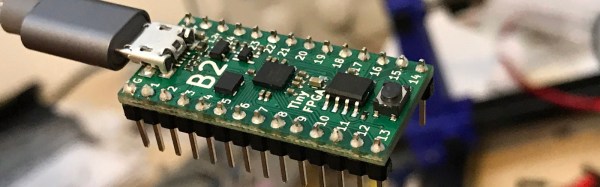

This protocol decoder is capable of looking at the ones and zeros on the data bus of a 6502-based computer. Right now, [hoglet] able to stream two million 6502 cycles directly to memory, so he’s able to capture the entire startup sequence of a BBC Micro. The hardware for this build was at first an Open Bench Logic Sniffer on a Papilio One FPGA board. This hardware was changed to an impressively inexpensive Cypress FX2 development board that was reconfigured to a 16 channel logic analyzer.

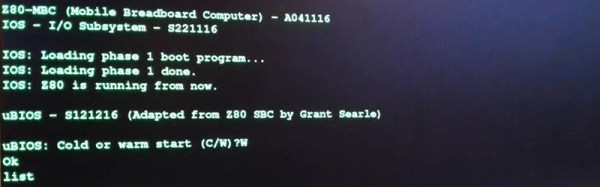

The software stack is where this really shines, and here [hoglet] documented most of the build over on the stardot forums. The basic capture is done with Sigrok, the Open Source signal analysis toolchain. This project goes a bit further than simply logging ones and zeros to a file. [hoglet] designed an entire 6502 protocol decoder with Python. Here’s something fantastic: this was [hoglet]’s first major Python project.

To capture the ones and zeros coming out of a 6502, the only connections are the eight pins on the data bus, RnW, Sync, Rdy, and Phy2. That’s only twelve pins, and no connections to the address bus, but the protocol decoder quickly starts to predict what the current program counter should be. This is a really fantastic piece of work, enabling an entire stack trace on any 6502 computer for less than $20 in parts.