Here’s a common story when it comes to password retrieval: guy sets up a PC, and being very security-conscious, puts a password on his Seagate hard drive. Fast forward a few months, and the password is, of course, forgotten. Hard drive gets shuffled around between a few ‘computer experts’ in an attempt to solve the problem, and eventually winds up on [blacklotus89]’s workbench. Here’s how he solved this problem.

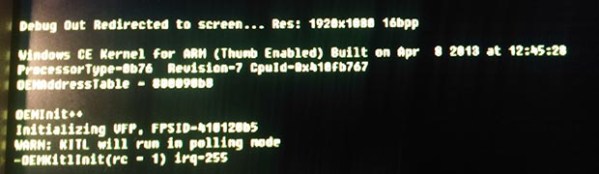

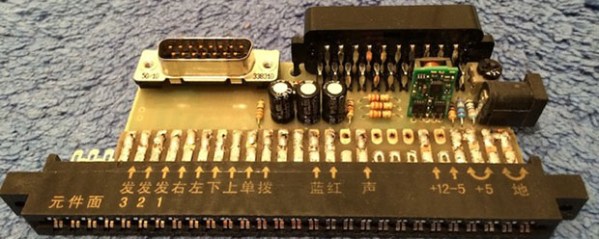

What followed is a walk down Hackaday posts from years ago. [blacklotus] originally found one of our posts regarding the ATA password lock on a hard drive. After downloading the required tool, he found it only worked on WD hard drives, and not the Seagate sitting lifeless on his desk. Another Hackaday post proved to be more promising. By accessing the hard drive controller’s serial port, [blacklotus] was able to see the first few lines of the memory and the buffer.

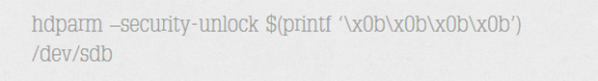

Two hours and two Python scripts later, [blacklotus] was able to dump the contents of his drive. He then took another Seagate drive, locked it, dumped it, and analyzed the data coming from this new locked drive. He found his old password and used the same method to look for the password on the old, previously impenetrable drive. It turns out the password for the old drive was set to ‘0000’, an apparently highly secure password.

In going through a few forums, [blacklotus] found a lot of people asking for help with the same problem, and a lot of replies saying. ‘we don’t know if this hard drive is yours so we can’t help you.’ It appears those code junkies didn’t know how to unlock a hard drive ether, so [blacklotus] put all his tools up on GitHub. Great work, and something that didn’t end up as a Hackaday Fail of the Week as [blacklotus] originally expected.