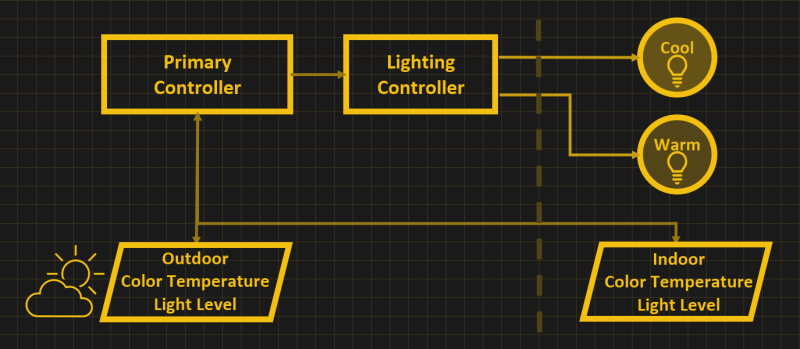

[Jon] wants his home office lighting to mimic the light outside, at least from a color perspective. To that end, he has embarked on a design which monitors both the outdoor light and at his work station, and accordingly drives a pair of LED lamps of different colors. One lamp is rated at above 5000 K and provides “cool” lighting, , and the other is rated at less than 3000 K for “warm” lighting.

Commercial solutions do exist, but they are proprietary and do this within a single bulb and seem difficult to control in an orchestrated manner throughout the house. [Jon] plans for his approach to be scalable, eventually consisting of a variety of lighted areas of the house from a single microcontroller.

One of the design goals for this project is to create something that could disappear into the room, rather than the science fair aesthetic of my prior project.

One commenter on his project’s site asked why [Jon] is doing this, that is, what is the value of controlling the color of your indoor lighting? While [Jon] doesn’t have a specific goal in mind at the moment, he notes that these techniques could potentially be helpful for enhancing productivity, managing circadian rhythms, and as light therapy for seasonal depression.

We covered [Jon]’s science-fair-like project that in this writeup from last year. If the topic interests you, check out the white papers he links on his project page for further reading.