Established FDM 3D printers designs generally lead themselves well to being scaled up, as long as you keep frame stiffness, alignment and movement in mind. [Ivan Miranda] needed a big printer for his big projects (videos below), so he built his own i3 style printer with a 800 mm × 500 mm usable print bed and about 500 mm vertical print height.

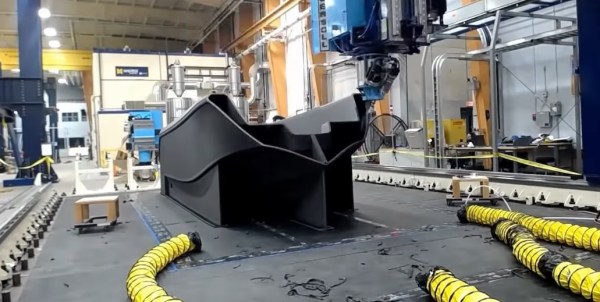

The frame of the new machine is built using 20×20 and 20×40 aluminium V-slot extrusions with some square tubing for reinforcement. To move all the weight, all 3 axes are driven by double NEMA17 steppers, via a DUET3D board with an expansion board for the extra motors. The extruder is the new E3D Hemera with a 0.8 mm nozzle. The print bed is a mirror, on top of the aluminium plate, headed by a large silicone heat pad. The first bed version used a smaller heat pad directly on the back of the mirror, but it heated up unevenly and the mirror ended up cracking. Look out for the ingeniously lightweight and simple cable management to the extruder. When all was said and done he printed a 800 mm long size 66 wrench as a test piece with zero warp, which is pretty good even for PLA. This project is also a perfect example of the power of 3D printing for rapid iterative development, as lot of the printed fittings went through multiple versions.

Although [Ivan] received most of the components for free, a printer like this is still within reach of the rest of us. We look forward to a lot of big prints by [Ivan] in his signature red, like a massive nerf gun and the ridable tank he is currently working on. Continue reading “Giant 3D Printer For Giant Projects”

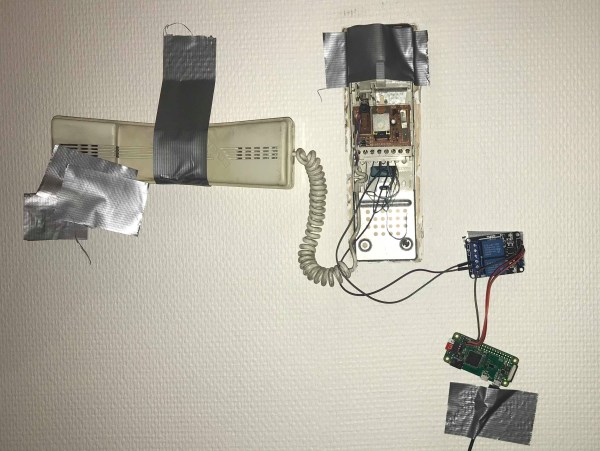

cut in half and hollowed out on a lathe. A beam sits on the centre line of the ball, mounted on a bearing in each half to allow the ball to spin around it. Steering done by shifting the centre of mass, by moving a steel pendulum that hangs below the beam side to side with heavy-duty servo. The servo is controlled with an Arduino, and an IMU to detects the balls orientation. Power is provided by and RC Lipo battery. The wireless controller is a sneaky little device that is taped to [Mark]’s back and covered with clothing, and steers the ball by detecting how far he leans with an IMU module. The brain is an Arduino Mini and an NRF24L01 provides the RF link.

cut in half and hollowed out on a lathe. A beam sits on the centre line of the ball, mounted on a bearing in each half to allow the ball to spin around it. Steering done by shifting the centre of mass, by moving a steel pendulum that hangs below the beam side to side with heavy-duty servo. The servo is controlled with an Arduino, and an IMU to detects the balls orientation. Power is provided by and RC Lipo battery. The wireless controller is a sneaky little device that is taped to [Mark]’s back and covered with clothing, and steers the ball by detecting how far he leans with an IMU module. The brain is an Arduino Mini and an NRF24L01 provides the RF link.