(Bipolar Junction) Transistors versus MOSFETs: both have their obvious niches. FETs are great for relatively high power applications because they have such a low on-resistance, but transistors are often easier to drive from low voltage microcontrollers because all they require is a current. It’s uncanny, though, how often we find ourselves in the middle between these extremes. What we’d really love is a part that has the virtues of both.

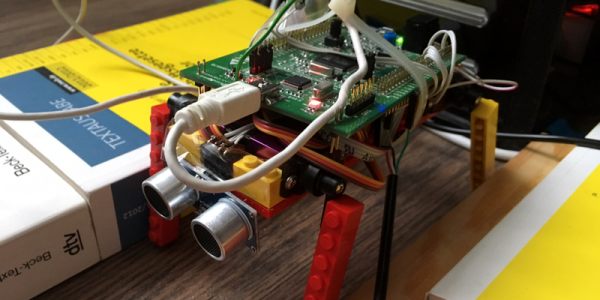

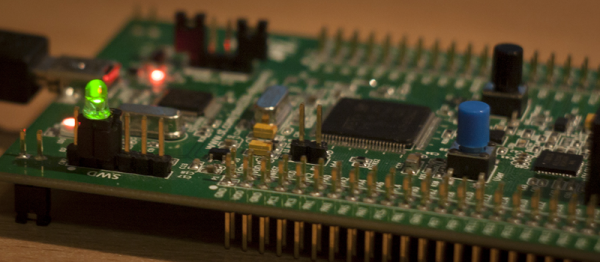

The ask in today’s Ask Hackaday is for your favorite part that fills a particular gap: a MOSFET device that’s able to move a handful of amps of low-voltage current without losing too much to heat, that is still drivable from a 3.3 V microcontroller, with bonus points for PWM ability at a frequency above human hearing. Imagine driving a moderately robust small DC robot motor forwards with a microcontroller, all running on a LiPo — a simple application that doesn’t need a full motor driver IC, but requires a high-efficiency, moderate current, and low-voltage-logic compatible transistor. If you’ve been here and done that, what did you use?