This year’s Hackaday Prize is off to a roaring start. And that’s fantastic, because this year’s challenge is a particularly important one: reducing mankind’s footprint on the earth through better energy collection, better resource use, and keeping what we’ve already got running a little bit longer. Not only is this going to be the central challenge for the next century, but it’s also a playground for hackers like us.

The first phase, Planet-Friendly Power, is in full swing, and we saw some entries on the first day! Were they cheating? Did they have inside information? Nope! Tons of hackers are working on energy efficient ways to drive their projects all along. If your Raspberry Pi data-logger can run on the fuel of the sun, it’s not only better for the world, but it’s a project that you don’t have to remember to change the batteries on.

The first phase, Planet-Friendly Power, is in full swing, and we saw some entries on the first day! Were they cheating? Did they have inside information? Nope! Tons of hackers are working on energy efficient ways to drive their projects all along. If your Raspberry Pi data-logger can run on the fuel of the sun, it’s not only better for the world, but it’s a project that you don’t have to remember to change the batteries on.

We’ve got a challenge on recycling, one on reverse engineering stuff to keep it out of the landfill, and one on environmental monitoring and communications infrastructure. These are all great hacker topics, and showcase how folks like us can do our small parts to keep the world running without running it into the ground.

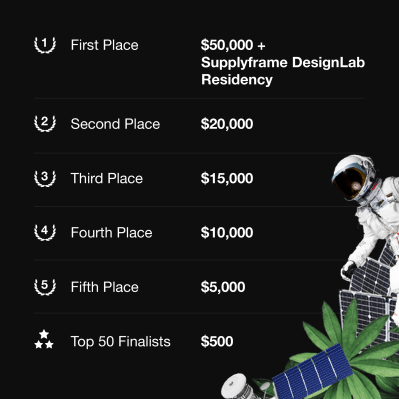

So all of you out there making mesh networks, optimizing solar projects, hacking open closed IoT networks to keep them from obsolescence, or building plastic-sorting robots, this is your chance to get some money and some recognition for your good work.

Thanks again to our Supplyframe overlords for consistently backing and believing in the purpose of the Hackaday Prize, and also to DigiKey who’s been a sponsor of the Prize many years running! Without them, we wouldn’t be able pull this off.

Hack the planet! (Non-ironically, and literally. And get money for doing it.) Hooray for the Hackaday Prize!