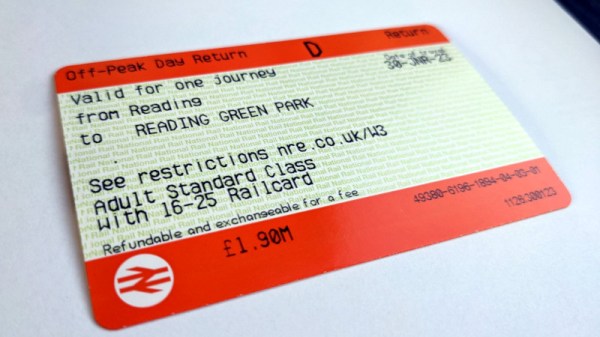

There was a time when to take a British rail journey was to receive a ticket barely changed since Victorian times — a small cardboard rectangle printed with the destination through which the inspector on the train would punch a hole. In recent decades these were replaced by credit-card-sized thin card, and now increasingly with scanable 2D codes from an app. These caught the attention of [eta], and she set about reverse engineering their operation.

The codes themselves are Aztec barcodes, similar to a QR code but with a single central fiducial mark. At first glance they resemble the codes used by non-UK ticketing systems, but she soon found out that they don’t follow the same standard. There followed a lengthy but fascinating trail of investigation, involving app decompilation of a dodgy copy of the ticket inspector app to find public keys, and then some work with a more reputably sourced app from another ticketing company.

Along the way it revealed a surprising amount of traveler data that maybe shouldn’t be in the public domain, and raises the question as to why the ticketing standard remains proprietary. It’s well worth a read.

If you’d like more UK rail ticket hacking, it formed the subject of a talk at EMF 2022.