[Scott Lambshed] took some time to shoot a video tour of egMakerSpace’s new digs. This hackerspace is located in East Gippsland Australia, which is to the East from Melbourne. We know the banner image we chose isn’t all that descriptive, but just look at all of that space! They’ve got a bounty of rooms to use for everything from crafts, to machine/wood shop, to retro computing. There’s even a nice outdoor patio area which was a bit overgrown to start with but cleanup has already begun.

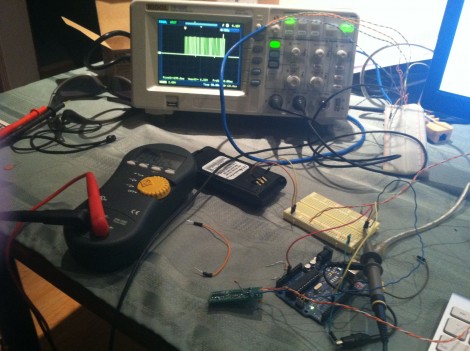

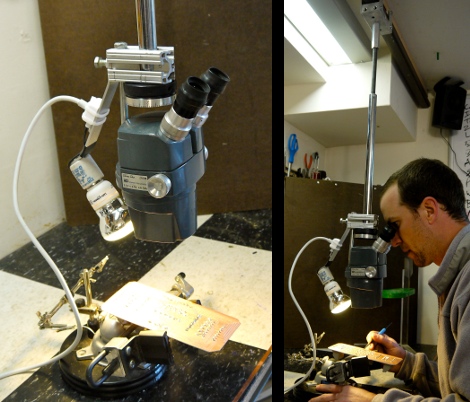

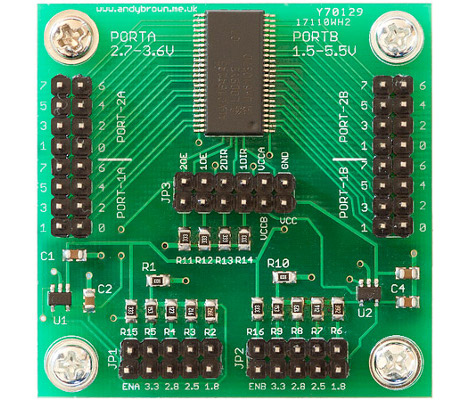

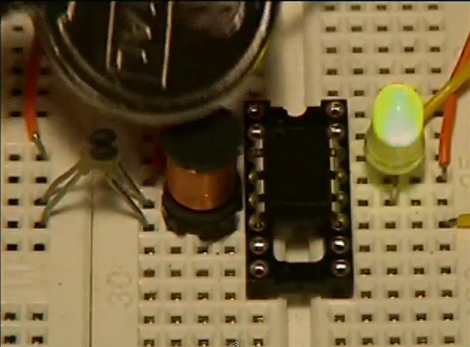

The group is just getting moved into what must have been an old hospital or school. Aside from some network infrastructure, a room full of couches, and a few tools, there’s not a lot in place yet. But one thing that is already looking quite good is their horde of electronics components. The latter half of the video shows boxes, bins, trays, and tackle boxes full of goodies just waiting to make it onto the next protoboard project.

[Scott] is hoping to get the word out in the area about egMakerSpace, and that’s exactly what these introductions are for. So grab you favorite video capture device and send us your own local hackerspace tour.

Continue reading “Hackerspace Intros: EgMakerSpace In East Gippsland Australia”

+

+