The history of making fire at will is a long and storied one, stretching back to the days when we’d rub wooden sticks together, or use flint and steel to ignite tinder. An easier, albeit vastly more expensive and dangerous alternative came in the 19th century when chemists discovered auto-ignition using a potassium chlorate mixture and sulfuric acid. This method was refined and later patented by Samuel Jones in 1828 as the ‘promethean match’ after the God of Fire, Prometheus, which is the topic of a recent [NurdRage] chemistry video.

Using practically the same recipe of potassium chlorate and sugar as in the 19th century, [NurdRage] uses paper straws to contain this powder. Glue is used to section the paper straw into two compartments and seal in the components, with the smaller compartment used for a glass capsule containing sulfuric acid. This vial was produced from the tip of a glass pipette, using a hot flame to first seal the tip, then detach and seal the other end of the tip, resulting in the sulfuric acid capsule, ready to be added to the second compartment.

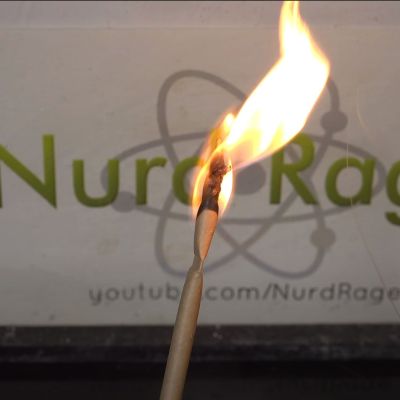

The moment this glass capsule is crushed, the sulfuric acid will soak into the paper, reaching the large compartment with the potassium chlorate and sugar mixture, causing a strongly exothermic reaction that ignites the paper. Yet as simple as this sounds, [NurdRage] found the three matches he made to be rather fickle, with one igniting beautifully after crushing the capsule with pliers, while one did nothing and the remaining match decided to violently explode rather than burn.

Considering the immense manual labor involved in making these matches, they never were very popular, and were quickly replaced by strike-anywhere matches, followed by safety matches, none of which require you to carry fragile glass capsules containing sulfuric acid with you. As a chemistry experiment, it is however a total blast that will set any boring chemistry class on fire.

Continue reading “Promethean Matches: The Ancestor To Modern Matches”