Despite a somewhat shaky start, it seems like everyone is finally embracing USB-C. Most gadgets have made the switch these days, and even Apple has (with some external persuasion) gotten on board. That’s great for new hardware, but it can lead to a frustrating experience when you reach for an older device and find a infuriatingly non-oval connector on the bottom.

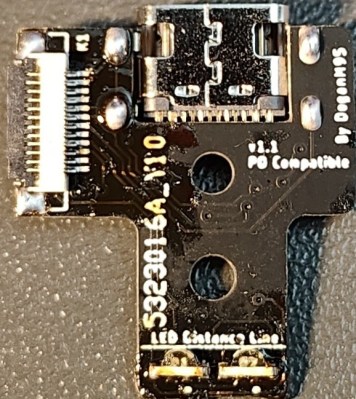

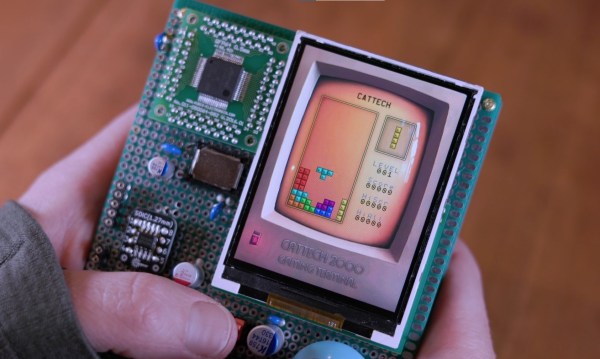

If one of those devices happens to be Sony’s DualShock 4 controller, [DoganM95] has the fix for you. Sony wisely put the controller’s original micro USB connector on a separate PCB so it could be cheaply replaced without having to toss the main PCB — that same modularity also means it was relatively easy to develop a USB-C upgrade board.

That said, there was a bit of a catch. The USB board on the DualShock 4 also carries a LED module that illuminates the “Light Bar” on the rear of the controller. In this design, [DoganM95] has replaced the original component with a pair of side-firing LEDs. Combined with the extra pins in the flexible printed circuit (FPC) connector necessary to control them, and the pair of 0603 resistors required for USB-C to actually provide power, putting this board together might take a bit more fine-pitch soldering than you’d expect.

Over the last couple of years, we’ve seen a wide array of devices receive DIY USB-C upgrades. In fact, this isn’t even the first time we’ve seen it done on the DualShock 4. But there’s something about hacking a modern port onto a legacy piece of hardware that we just can’t seem to get enough of.