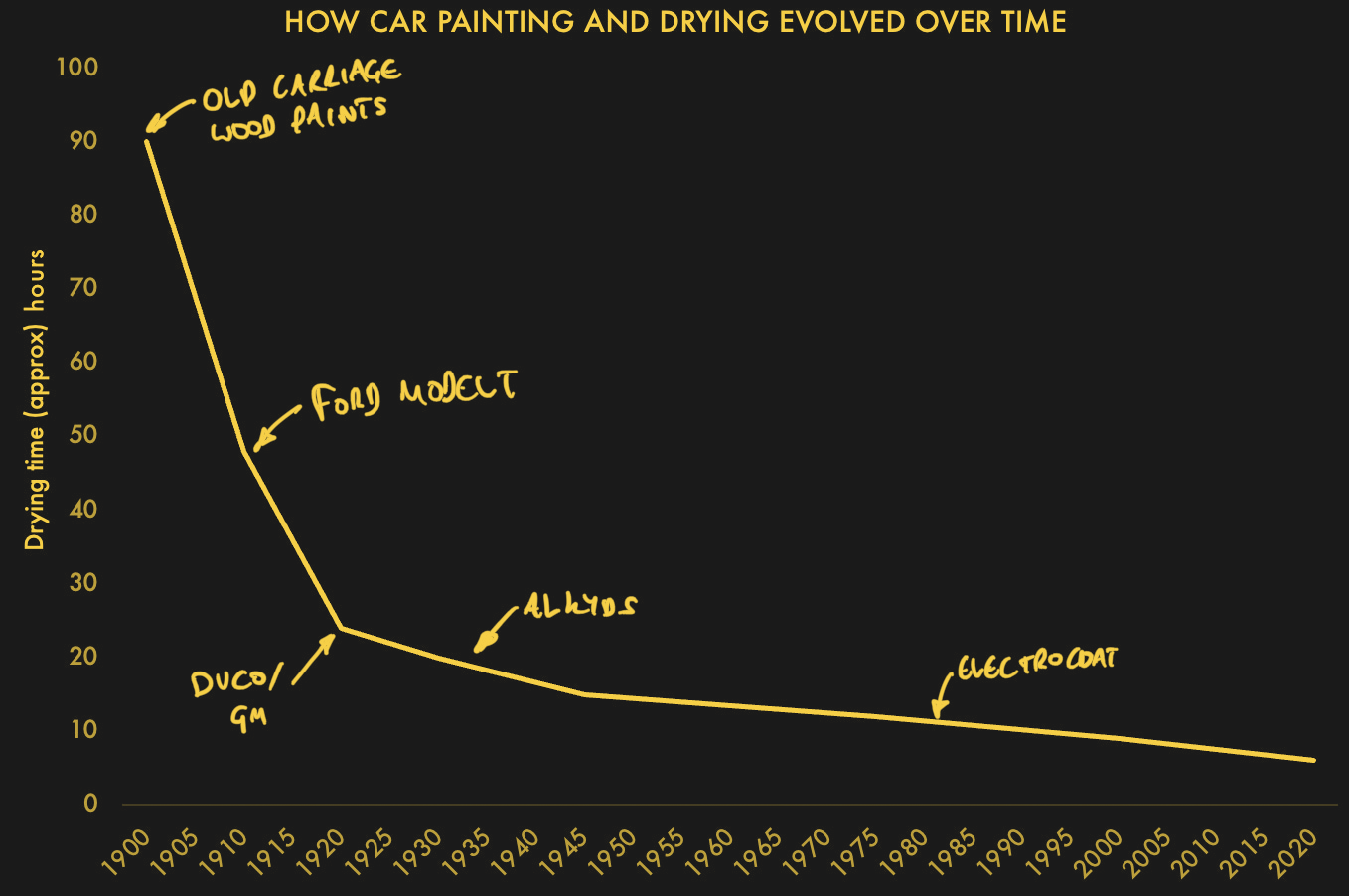

A Model T Ford customer could famously get their car “in any color he wants, so long as it’s black.” Thus begins [edconway]’s recounting of the incremental improvements in car paint and its surprising role in mass production, marketing, and longevity of automobiles.

In it, we learn that the aforementioned black paint from Ford had so much asphalt in it that black was the only color that would work. Not to go down a This Is Spinal Tap rabbit hole, but there were several kinds of black on those Model Ts. Over 30 of them were used for various purposes. The paints also dried in different ways. While the assembly only took 12 hours, the paint drying time took days, even weeks backing up production and begging for innovation. [edconway] then fast-forwards to an era of “conspicuous consumption and ‘planned obsolescence’” with DuPont’s invention of Duco that brought color to the world of automobiles.

See the article for the real story of advances in paint technology and drying time. Paint application technology has also steadily improved over the years, so we recommend diving in to get the century’s long story.