One of the global news stories this week has been the passing of the British monarch, Queen Elizabeth II. Since she had recently celebrated 70 years on the throne, the changing of a monarch is not something that the majority of those alive in 2022 will have seen. But it’s well known that there are a whole suite of “London Bridge has fallen” protocols in place for that eventuality which the various arms of the British government would have put in motion immediately upon news from Balmoral Castle. When it became obvious that the Queen’s health was declining, [Hackerfantastic] took to the airwaves to spot any radio signature of these plans. [Update 2022-09-11] See the comments below and a fresh Tweet to clarify, it appears these were not the signals they were at first suspected to be.

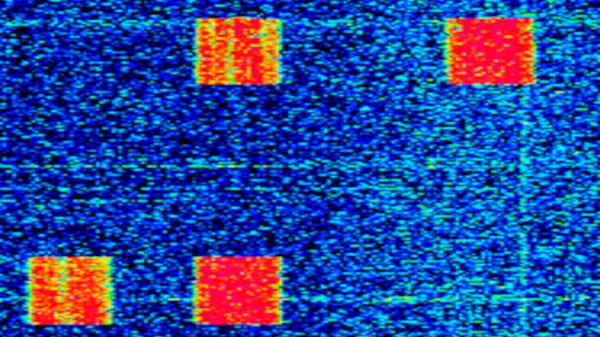

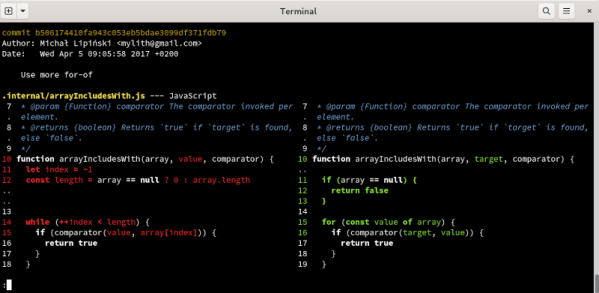

What he found in a waterfall view of the 4 MHz military band was an unusual transmission, a set of strong QPSK packets that started around 13:40pm on the 8th of September, and continued on for 12 hours before disappearing. The interesting thing about these transmissions is not that they were a special system for announcing the death of a monarch, but that they present a rare chance to see one of the country’s Cold War era military alert systems in action.

It’s likely that overseas embassies and naval ships would have been the intended recipients and the contents would have been official orders to enact those protocols, though we’d be curious to know whether 2022-era Internet and broadcast media had tipped them off beforehand that something was about to happen. It serves as a reminder: next time world news stories happen in your part of the world, look at the airwaves!