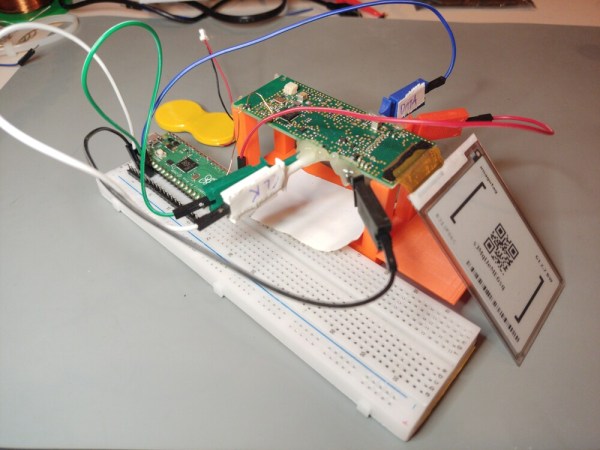

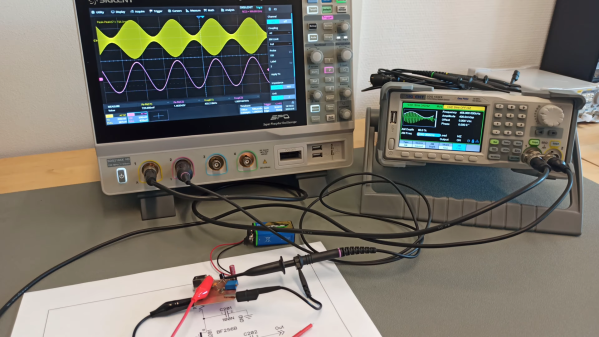

We’ve seen a number of people create plasma speakers over the years here at Hackaday, so at first blush, the latest Plasma Channel video from [Jay Bowles] might seem like more of the same. Even his overview of the assembly of the 555 timer circuit at the heart of the setup, as detailed as it may be, is something we’ve seen before.

But the back half of the video, where [Jay] talks about the flyback transformer used in this plasma speaker, really got our attention. You see, frustrated by the limited options on the market for AC flybacks, he set out to put together a custom transformer utilizing a 3D printed secondary former of his own design.

Armed with a spare core, [Jay] spent some time in CAD coming up with his secondary. Despite never having built a flyback before, his first attempt managed to produce some impressive sparks — that is, until it arced through the printed plastic and released the critical Magic Smoke. Inspired by this early success, he went back to the digital drawing board and cranked his way through several different iterations until he came up with one that didn’t self-destruct.

Continue reading “Playing Music On A Custom Flyback Transformer”