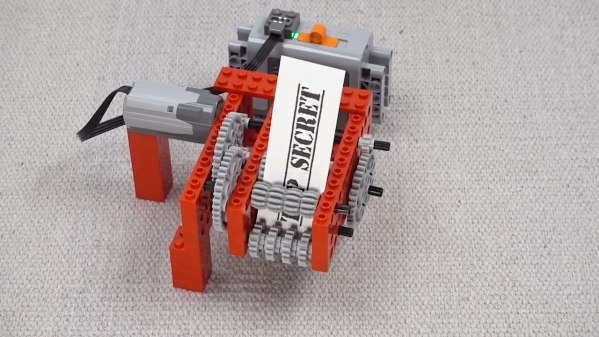

Sometimes we need to destroy documents before throwing them away for security reasons, and shredders are a primary way of achieving that. If you don’t have your own, you might consider building your own, like [Brick Experiment Channel] did using Lego.

First attempts at shredding a small slip of paper with interlocking gears were a failure, merely crumpling the paper in an attractive rippled manner. As the “Top Secret” piece of paper says, “If you can read this, the shredder didn’t work.” Adding more gears managed to gouge a couple holes in the paper, but it was still far from effective. Continuing down this path further only stalled the Lego motor.

A redesign with different sized gears did eventually manage to tear the paper into large chunks. One set of gears would hold on to the paper while a following set would tear away a section. A further modification combined this method with using bevel gears as a sort of blade, and improved shredding performance further, to the point where the paper was torn into satisfyingly tiny fragments.

It’s a fun little build, even if it won’t come close to taking on a full page of A4. It’s a great example of what can be achieved when you set a simple goal with readily measurable outcomes, in this case, the legibility of the original message on the paper.

We’ve seen a few shredders around here before too. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Building A Lego Paper Shredder”