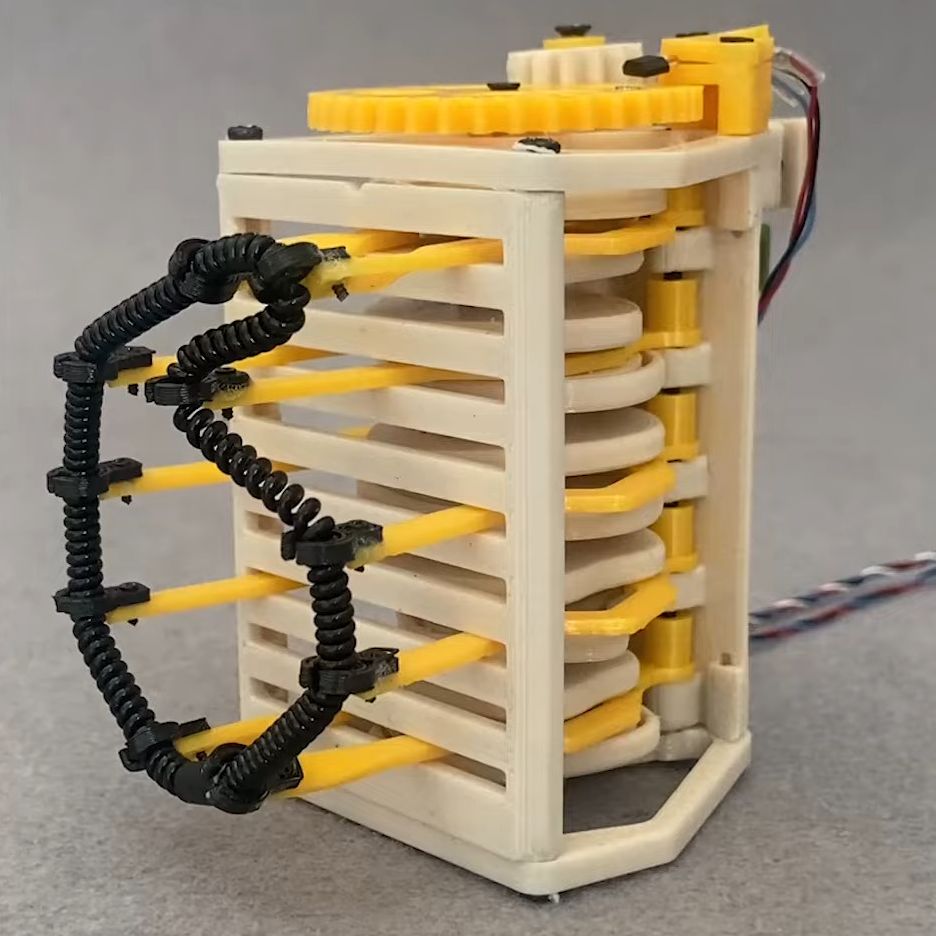

The Enigma machine is perhaps one of the most legendary devices to come out of World War II. The Germans used the ingenious cryptographic device to hide their communications from the Allies, who in turn spent an incredible amount of time and energy in finding a way to break it. While the original Enigma was a complicated electromechanical contraption, [DrMattRegan] recently set out to show how its operation can be replicated with an EPROM.

The German Enigma machine was, for the time, an extremely robust way of coding messages. Earlier versions proved somewhat easy to crack, but subsequent machines added more and more complexity rendering them almost impenetrable. The basis of the system was a set of rotors which encrypted each typed letter to a different one based on the settings and then advanced one place in their rotation, ensuring each letter was encrypted differently than the last. Essentially this is a finite-state machine, something perfectly suited for an EPROM. With all of the possible combinations programmed in advance, an initial rotor setting can be inputted, and then each key press is sent through the Enigma emulator which encrypts the letter, virtually advances the rotors, and then moves to the next letter with each clock cycle.

[DrMattRegan]’s video, also linked below, goes into much more historical and technical detail on how these machines worked, as well as some background on the British bombe, an electromechanical device used for decoding encrypted German messages. The first programmable, electronic, digital computer called Colossus was also developed to break encrypted Enigma messages as well, demonstrating yet another technology that came to the forefront during WWII.