[Engineering After Hours] wanted a highly maneuverable robot chassis with a tight turning radius. Skid steering seemed to be the perfect solution, but the available commercial options didn’t take his fancy. Thus, a custom build was the answer – with impressive results.

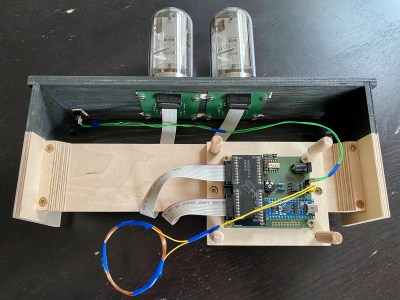

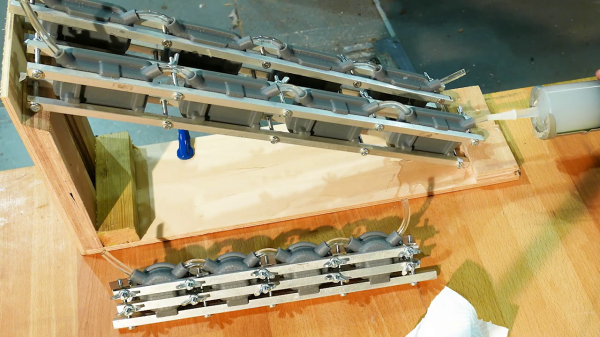

The build packs two large RC motors, one for each side, with each driving two wheels through a belt drive. This reduces the electronics required to the bare minimum for skid steering. It’s all assembled within a plasma-cut metal chassis which is more than tough enough to take some hard knocks.

One of the primary goals on the build was to eliminate the risk of vibrations and shock damaging the motors and gearboxes. Many off-the-shelf designs couple the wheels directly to gearbox output shafts, potentially damaging the expensive components over time. In this design, a separate bearing assembly is used to take the load from the wheels instead.

It’s a great example of how an engineering-first approach can build a sturdy ‘bot with a minimum of fuss. Outfitted with some fat off-road tyres the performance is impressive, with the ‘bot having no trouble tearing it up in mud, snow, and water.

We’ve seen other great builds from [Engineering After Hours] before, like the active aero RC build. Video after the break.