Houston’s historic third ward, aka “The Tre,” is ripe rife with history, and some of that history is digitally preserved and accessible through an art installation in the form of repurposed payphones. We love payphones for obvious reasons and seeing them alive and kicking warms our hearts. Packing them with local history checks even more boxes. Twenty-four people collaborated to rebuild the three phones which can be seen in the video after the break, including three visual artists, three ambassadors, and eighteen residents who put their efforts into making the phones relevant not only to the ward but specifically to the neighborhood. One phone plays sound clips from musicians who lived or still live in the ward, another phone has spoken word stories, and the third has field recordings from significant locations in The Tre.

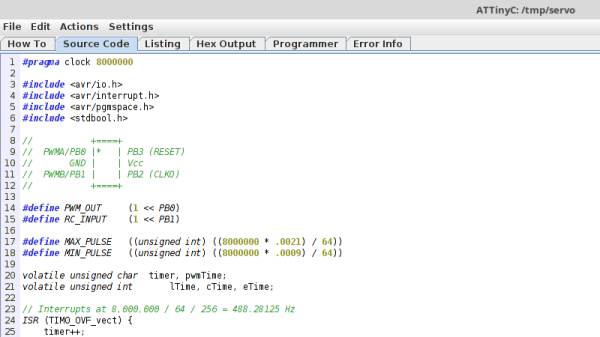

Each phone is powered by a solar cell and a USB battery pack connected to a Teensy with an audio adapter board, and a 20 watt amplifier. Buttons 1-9 play back recorded messages exclusive to each phone, star will record a message, and zero will play back the user-recorded message. Apps for smart phones are easy for young folks to figure out but the payphones ensure that these time capsules can be appreciated by people of any age, regardless of how tech savvy they are and that is wise as well as attractive. The coin return lever and coin slot also have associated sound clips unlike regular payphones so the artists get extra credit.

Did we say that we love payphones? Yes, yes we did. The very first post on Hackday was for a redbox and that got the ball rolling.