There is a long history of Visual or Graphical Programming Languages, and most of them make more sense than the name of Microsoft’s Visual Basic, C#, and Visual Studio IDE. Some people don’t like to code, and for them, graphical programming languages replace semicolons and brackets with easy-to-understand boxes and wires.

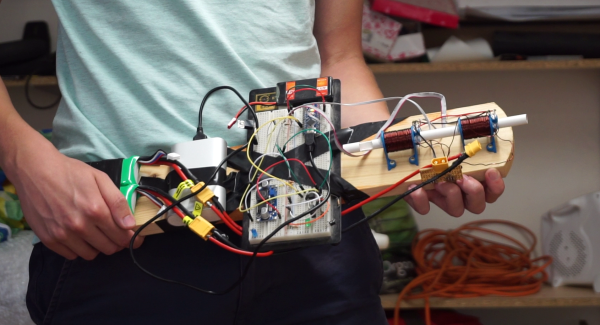

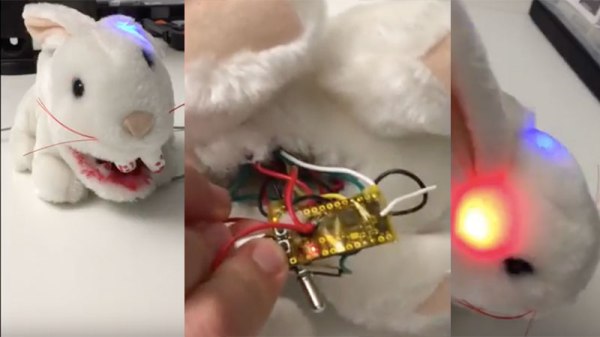

This Friday, we’re going to be talking about graphical programming languages with [Boian Mitov]. He’s a software developer, founder of Mitov Software, and the creator of Visuino, a graphical programming language for the embedded domain. Everything from the Arduino to Teensy, ESP8266, ESP32, the chipKIT, and Maple Mini are supported with this IDE. It’s a simple drag-and-drop way of programming microcontrollers that Scratches an itch (see what I did there?) for an easy way to introduce non-programmers to the embedded world and also provides a faster way to build custom applications.

This Friday, we’re going to be talking about graphical programming languages with [Boian Mitov]. He’s a software developer, founder of Mitov Software, and the creator of Visuino, a graphical programming language for the embedded domain. Everything from the Arduino to Teensy, ESP8266, ESP32, the chipKIT, and Maple Mini are supported with this IDE. It’s a simple drag-and-drop way of programming microcontrollers that Scratches an itch (see what I did there?) for an easy way to introduce non-programmers to the embedded world and also provides a faster way to build custom applications.

When it comes to graphical programming languages, we can’t find a better Hack Chat guest than [Boian]. He’s the author of the OpenWire dataflow processing technology — another graphical programming language –, the IGDI+ library, VideoLab, SignalLab, AudioLab, PlotLab, InstrumentLab, and author of VCL for Visual C++. He’s a regular contributor to Blaise Pascal Magazine, too.

During this Hack Chat, we’ll be discussing what makes Visual Programming worth it, how and why it works, when it doesn’t and how to develop a graphical programming language. Visuino will be of special interest, And I’m sure someone will work in a, ‘what’s happening with Max/MSP under Ableton’ question. If you have a question for [Boian], here’s a question sheet to guide the discussion.

Here’s How To Take Part:

Our Hack Chats are live community events on the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This Hack Chat will take place at noon Pacific time on Friday, August 11th. Here’s a time and date converter!

Our Hack Chats are live community events on the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This Hack Chat will take place at noon Pacific time on Friday, August 11th. Here’s a time and date converter!

Log into Hackaday.io, visit that page, and look for the ‘Join this Project’ Button. Once you’re part of the project, the button will change to ‘Team Messaging’, which takes you directly to the Hack Chat.

You don’t have to wait until Friday; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.