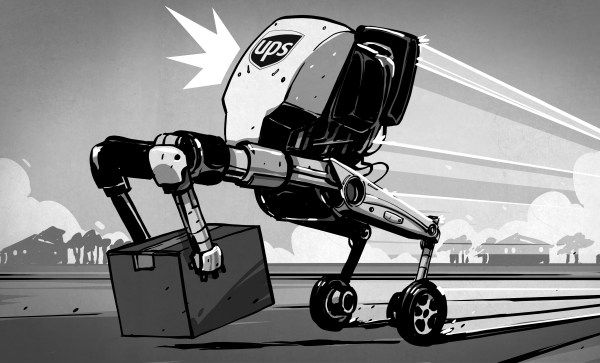

You’ve no doubt by now seen Boston Dynamics latest “we’re living in the future” robotic creation, dubbed Handle. [Mike Szczys] recently covered the more-or-less-official company unveiling of Handle, the hybrid bipedal-wheeled robot that can handle smooth or rugged terrain and can even jump when it has to, all while remaining balanced and apparently handling up to 100 pounds of cargo with its arms. It’s absolutely sci-fi.

[Mike] closed his post with a quip about seeing “Handle wheeling down the street placing smile-adorned boxes on each stoop.” I’ve recently written about autonomous delivery, covering both autonomous freight as the ‘killer app’ for self-driving vehicles and the security issues posed by autonomous delivery. Now I want to look at where anthropoid robots might fit in the supply chain, and how likely it’ll be to see something like Handle taking over the last hundred feet from delivery truck to your door.

Continue reading “Autonomous Delivery And The Last 100 Feet”