When the second band had played its last encore, before the legendary DJ took the stage, a cadre of hardware hackers climbed three steps with a twinkle in their eyes and glowing electronics in their hands. I’m surprised and relieved that the nugget of excitement that first led me to twiddle a byte in a microcontroller is still alive, and this moment — this crossroads of hacker family — stirred that molten hot center of adventure in everyone.

The badge hacking demoscene is a welcoming one. No blinking pixel is too simple, and no half-implemented idea falls short of impressing everyone because they prove the creativity, effort, and courage of each who got up to share their creation. How could we ever get together as a community and not do this?

It was after midnight before we began the demoparty. I somehow managed to come to the Hackaday | Belgrade conference without a USB webcam to use as a top-down camera. I also didn’t line up someone to record with a camera until minutes before. Please forgive our technical difficulties — we first tried to use a laptop webcam to project to the bigscreen. When that failed, focusing on the badges because tough for our ad-hoc camera operator. This video is a hack, but I think it’s worth looking past its tech problems.

The crowd gathered as close to the stage as possible and there was electricity in the audience as the wiles of the day were explained. Join me after the break for a brief rundown of each demo, along with a timestamp to find it in the video.

Continue reading “128 LEDs, 5 Buttons, IR Comm, And A Few Hours: What Could You Create?”

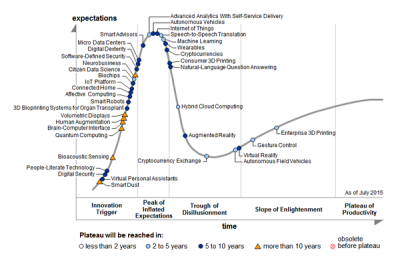

Depending on whom you ask, the IoT seems to mean that whatever the thing is, it’s got a tiny computer inside with an Internet connection and is sending or receiving data autonomously. Put a computer in your toaster and

Depending on whom you ask, the IoT seems to mean that whatever the thing is, it’s got a tiny computer inside with an Internet connection and is sending or receiving data autonomously. Put a computer in your toaster and