Looking for a way to spruce up your place with a touch of rustic-future-deco? Why not embed LEDs somewhere they were never designed for? [Callosciurini] had a nice chunk of oak and decided to turn it into a lamp.

He was inspired by a similar lamp that retails for over $1,000, so he figured he would make his own instead (business idea people?). The oak is a solid chunk measuring 40x40x45cm and what he did was route out an angled channel across all faces of the cube. This allowed him to installed a simple LED strip inside the groove — then he filled it with an epoxy/paint mix to give it that milky glow.

To finish it off he sanded the entire thing multiple times, oiled the wood, and sanded it again with a very fine grit. The result is pretty awesome.

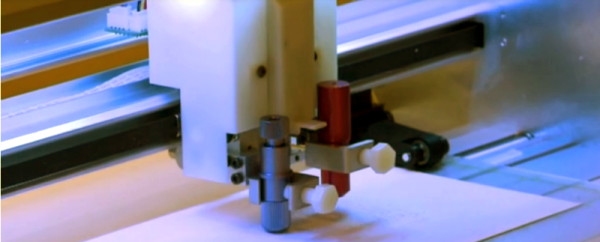

Now imagine what you could do design-wise if you could fold wood to make a lamp? Well with this custom wood-folding saw-blade, the sky is the limit!

[via r/DIY]