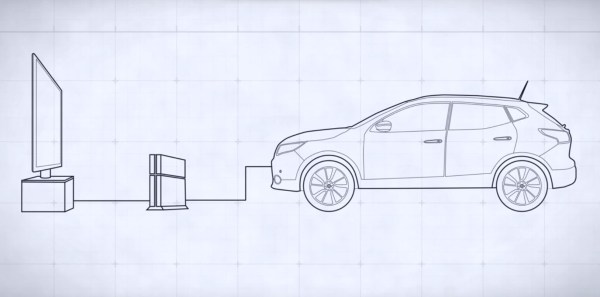

For a rather obscure brand advertisement, Nissan decided to turn one of their cars into a giant Playstation 4 controller to play a game of football (soccer).

The first question to pop into our heads was why? And that’s because Nissan is a major sponsor of UEFA Champions League. From there, it became why not? We love the companies that get their hands dirty on a hacking level, and actually do something instead of just funneling money into your standard billboard advertising — it’s just more fun this way.

The second question you should be asking yourself is how do you play soccer using a car? Well, it’s pretty simple. Steering is your left and right controls, the indicator switch is forward and backward, the windshield wipers kick the ball, a steering wheel button lets you run faster, the brake pedal passes the ball, and the gas pedal shoots. Simple right? As one of the prototype testers describes:

It’s kinda like tapping your head and rubbing your stomach at the same time, it really messes your head up — but it’s really enjoyable when you get it right.

Continue reading “Turning A Car Into A Playstation Controller”