As the maker movement has exploded in popularity in recent years, there has been a strong push to put industrial tools into the hands of amateur tinkerers and hackers. CNC mills, 3D Printers, and laser cutters were all extremely expensive machines that were far too costly for most people until makers demanded them and hackers found ways to make them affordable. But, aside from the home brewing scene, those advancements haven’t really touched on anything organic. Which is a deficiency that Amino, a desktop bioengineering system, is seeking to address.

Amino, created by [Julie Legault], is currently seeking crowd-funding via Indiegogo. Hackaday readers are more suspicious than most when it comes to crowd-funding campaigns, and with good reason. But, [Julie Legault] has some very impressive credentials that lend her a great deal of credibility. She has four degrees in the arts and sciences, including a Masters of Science at the MIT Media Lab.

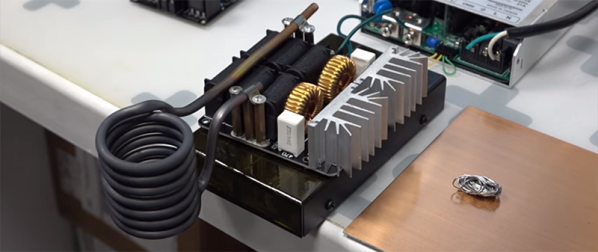

It was for that degree at MIT that [Julie] started Amino as her thesis. Her plan is to bring the tools necessary for bioengineering to the masses – tools which are traditionally only available in research labs. Those tools are packaged into a small desktop-sized unit called Amino. Backers will receive this desktop system, along with the supplies for their first project. Those projects are predefined, but the tools are versatile enough to allow users to move on to their own projects in the future. [Julie] thinks that the future is in bioengineering, and that the best way to feed innovation is to make the necessary tools both affordable and accessible.

Continue reading “Amino Wants To Bring Bioengineering To Your Workbench”