Hackaday Europe is on again for 2024, and we couldn’t be more excited! If you’re a European hacker, and have always wanted to join us up for Supercon in the states, here’s your chance to do so without having to set sail across the oceans. It’s great to be able to get together with our continental crew.

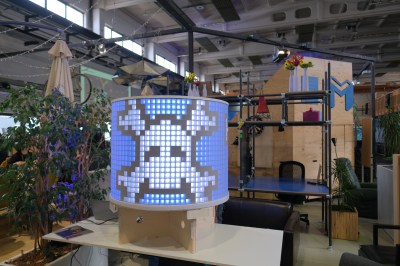

Just like last time, we’ll be meeting up in Berlin at Motionlab, Bouchestrasse 12 for a weekend of talks and workshops. On paper, the event runs April 13th and 14th, but if you’re in town on Friday the 12th, we’ll be going out for drinks and socializing beforehand. Saturday starts up at 9 AM and is going to be full of presentations, with food throughout and our own mix of hacking and music running until 2 AM. Sunday starts up a little bit later with brunch and as many lightning talks as we can fit into the afternoon.

Just like last time, we’ll be meeting up in Berlin at Motionlab, Bouchestrasse 12 for a weekend of talks and workshops. On paper, the event runs April 13th and 14th, but if you’re in town on Friday the 12th, we’ll be going out for drinks and socializing beforehand. Saturday starts up at 9 AM and is going to be full of presentations, with food throughout and our own mix of hacking and music running until 2 AM. Sunday starts up a little bit later with brunch and as many lightning talks as we can fit into the afternoon.

And as always, we want you to bring a project or two along to show and tell. Half the fun of an event like this, where everyone is on the same wavelength, is the mutual inspiration that lurks in nearly every random conversation. It’s like Hackaday, but in real life!

So without further ado: get your tickets right here! We have a limited number of early-bird tickets at $70, and then the remainder will go on sale for $142 (plus whatever fees).

Call for Participation

So who is going to be speaking at Hackaday Europe? You could be! We’re also opening up the Call for Participation right now, both for talks and for workshops. Whether you’ve presented your work live before or not, you’re not likely to find a more appreciative audience for epic hacks, creative constructions, or you own tales of hardware, firmware, or software derring-do.

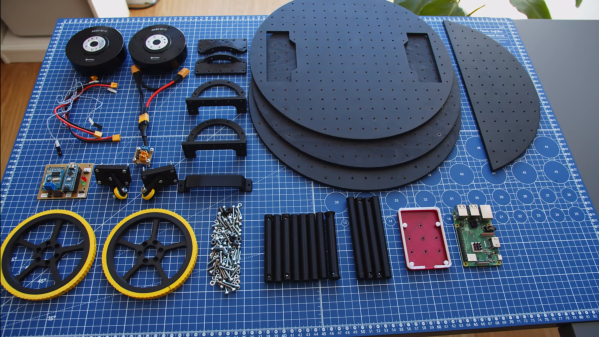

Workshop space is limited, but if you want to teach a group of ten or so people your favorite techniques or build up a swarm of small robots, we’d love to hear from you.

All presenters get in free, of course, and we’ll give you an early-bird price even if we can’t fit you into the schedule. So firm up what you’d like to share, and get your proposal in before Feb 22.

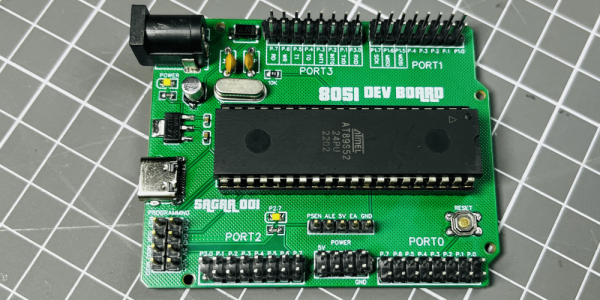

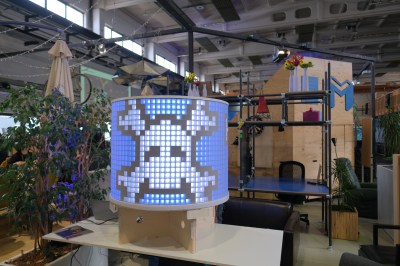

The Badge

Part of the fun of an event like this is sharing what you’re working on with a rare like-minded crowd. True story: we came into last year’s Hackaday Berlin event with a raw idea for our own Superconference badge, that we needed to have done by November. Talks with [Schneider] about the lovely badge for the Chaos Communications Camp inspired us to use those sweet round screens, and a chat with [Stefan Holzapfel] convinced us of the possibility to run an audio DAC at DC.

Part of the fun of an event like this is sharing what you’re working on with a rare like-minded crowd. True story: we came into last year’s Hackaday Berlin event with a raw idea for our own Superconference badge, that we needed to have done by November. Talks with [Schneider] about the lovely badge for the Chaos Communications Camp inspired us to use those sweet round screens, and a chat with [Stefan Holzapfel] convinced us of the possibility to run an audio DAC at DC.

So it’s fitting that we’ll be bringing the Vectorscope badge to Berlin, with some new graphics of course. If you didn’t catch it at Supercon, it’s a emulation of an old-timey X-Y mode oscilloscope and a DAC to drive it in software. Folks had a great time hacking it at Supercon, and you will too. It’s analog, it’s digital, and it’s got room for a lot of art. We’d love to see what you bring to it!

Thanks and See You Soon!

Of course, we can’t put on an event like this without help from our fantastic sponsors, so we’d like to say thanks to DigiKey for sponsoring not only the stateside Superconference, but also Hackaday Europe 2024. And as always, thanks to Supplyframe for making it all possible.

April is coming up fast, so get your proposals in and order your tickets now! We can’t wait to see you all.