Non-planar layer Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) is any form of fused deposition modeling where the 3D printed layers aren’t flat or of uniform thickness. For example, if you’re using mesh bed leveling on your 3D printer, you are already using non-planar layer FDM. But why stop at compensating for curved build plates? Non-planar layer FDM has more applications and there are quite a few projects out there exploring the possibilities. In this article, we are going to have a look at what the trick yields for us.

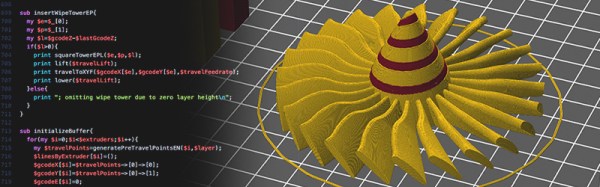

3D Printering: G-Code Post Processing With Perl

Most of our beloved tools, such as Slic3r, Cura or KISSlicer, offer scripting interfaces that help a great deal if your existing 3D printing toolchain has yet to learn how to produce decent results with a five headed thermoplastic spitting hydra. Using scripts, it’s possible to tweak the little bits it takes to get great results, inserting wipe or prime towers and purge moves on the fly, and if your setup requires it, also control additional servos and solenoids for the flamethrowers.

This article gives you a short introduction in how to post-process G-code using Perl and Slic3r. Perl Ninja skills are not required. Slic3r plays well with pretty much any scripting language that produces executables, so if you’re reluctant to use Perl, you’ll probably be able to replicate most of the steps in your favorite language.

Continue reading “3D Printering: G-Code Post Processing With Perl”

3D Printering: Makerbot’s Class Action Suit Dismissed

This time last year, Stratasys, parent company of Makerbot, was implicated in a class action suit. Investors claimed Stratasys violated securities laws, and overstated both the performance of the 5th generation of Makerbot printers and the performance of the company itself. Court docs received by Adafruit have revealed this case has been dismissed with prejudice. Makerbot won this one.

The case presented by Stratasys investors relied on two obvious facts. First, the price of Stratasys shares fell far beyond expectations. Second, the extruder for the 5th generation of Makerbot printers – the ‘Smart Extruder’ – was terrible. No one can reasonably dispute these claims; shares of SYSS fell from $120 in September of 2014 to $30 in September of 2015. With many returns to handle, Makerbot quickly redesigned the Smart Extruder.

Both of these indisputable facts are in stark contrast to statements made by Stratasys and Makerbot at the time. In a press release for the 4th quarter 2013 financial results, Stratasys’ expected sales to grow at least 25% over 2013 and stated it was experiencing “strong sales” of its desktop 3D printer. Concerning the Smart Extruder, Makerbot stated this new feature of the 5th generation Makerbots would make them easy to use, and “define the new standard for quality and reliability.”

The facts of this case are not in dispute – Stratasys did not see the growth they expected in late 2013. The Smart Extruder certainly did not make printers more reliable. These facts, however, are not sufficient to violate securities law. In a wonderful legal turn of phrase, the judge deciding this case called the statements about the quality of the 5th generation Makerbots consisted of, “non-actionable puffery,” and a ‘statement so vague and such obvious hyperbole than no reasonable investor would rely on them.’

Statements made by Stratasys on their financial performance were also found not to be sufficient to violate securities laws. Stratasys did make several statements about negative performance in late 2014 and 2015, and positive statements made earlier did not have an intent to deceive investors.

This is good news for Makerbot. The claims brought by investors in this case had little merit. The case cannot be appealed, and Stratasys is no longer facing a class action suit. Does this news actually matter? Not really; Makerbot is a dead man walking, and 2016 sales will be at levels not seen since 2010 or 2011.

The consumer 3D printing industry is booming, despite the Makerbot bellwether though.

3D Printering: The Makerbot Class Action Suit

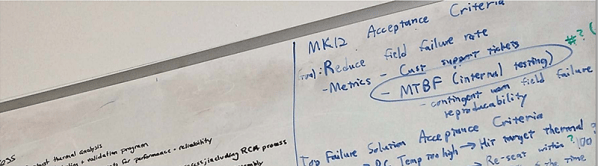

Since the 5th generation of Makerbot 3D printers were released at CES in 2014, there has been an avalanche of complaints about the smart extruder in these printers. Clogs were common, and the recommended fix was to simply replace the extruder. The smart extruder is a $175 part, and the mean time before failure is somewhere between 200 and 500 hours. With these smart extruders, you’re looking at a new extruder every dozen prints or so. Combine this with Makerbot’s abdication of open source values, and it’s easy to see why no one in the know would buy a Makerbot.

The performance of the 5th gen Makerbots is also reflected in the Stratasys stock price. The stock has tanked, from a high of $130.83 in early 2014 to a low of $31.88 a few days ago. This has investors calling for blood, and now there’s a class action suit claiming Stratasys violated securities laws. The court docs found by the folks at Adafruit allege Stratasys rushed the 5th gen Makerbots into production resulting in an avalanche of negative feedback, warranty claims, returns, and misled investors until the stock collapsed when the market was made aware of these issues.

The court documents allege Stratasys and Makerbot touted the incredible ease of use and ‘unmatched’ quality of the 5th generation of Makerbots, while former Makerbot employees confirmed known issues with the smart extruder. The 5th gen Makerbots were rushed into production without proper testing for performance and reliability and no standardized testing and validation program. In short, Makerbot itself didn’t know how bad the smart extruder was, but shipped the product anyway. This in turn hurt sales, with one sales executive leaving the company as he “did not want to sell the 5th generation printers after learning about the defect issues because he has a ‘conscience’.”

Despite this, those in charge at Makerbot and Stratasys continued to make misleading positive claims about the reliability of their printers and how the printers were received by the market. This is the crux of the lawsuit, and something that points to an artificially inflated stock value.

The plaintiffs for this lawsuit are limited to Stratasys stock holders, and anyone out there who only owns a 5th gen Makerbot will sadly be ignored in this lawsuit. Still, if the claims of this lawsuit are true, Stratasys and Makerbot are in for a world of hurt; this is an alleged violation of federal securities laws. demanding a jury trial. Popcorn abounds, and as always, [Zach] and [Adam] came out ahead.

3D Printering: Maker Faire And Resin Printers

Of course Maker Faire was loaded up with 3D printers, but we’re no longer in the era of a 3D printer in every single booth. Filament-based printers are passé, but that doesn’t mean there’s no new technology to demonstrate. This year, it was stereolithography and other resin-based printers. Here’s the roundup of each and every one displayed at the faire, and the reason it’s still not prime time for resin-based printers.

Formlabs

Formlabs

Of course the Formlabs Form 1+ was presented at the Bay Area Maker Faire. They were one of the first SLA printers on the market, and they’ve jumped through enough legal hoops to be able to call themselves the current kings of low-cost laser and resin printing. There were a few new companies and products at the Faire vying for the top spot, and this is where things get interesting.

The folks at Formlabs displayed the only functional print of all the resin-based 3D printing companies – a tiny, tiny Philco Predicta stuffed with an LCD displaying composite video. The display is covered by a 3D printed lens/window. That’s the closest you’re going to get to an optically clear 3D printed part at the Faire.

XYZPrinting Nobel

XYZPrinting, the company famous for the $500 printer that follows the Gillette model: sell the printer cheap, sell expensive replacement filament cartridges, and laugh all the way to the bank. Resetting the DRM on the XYZPrinting Da Vinci printer is easy, the proprietary host software is done away with, and bricked devices are not. Time for a new market, huh?

Enter the XYZPrinting Nobel, a resin printer that uses lasers to solidify parts 25 microns at a time. The build volume is 125x125x200mm (5x5x7.9″), with an X and Y resolution of 300 microns. Everything prints out just as you would expect. As far as laser resin printers go, it’s incredibly cheap: $1500. It does, however, use XYZware, the proprietary toolchain forced upon Da Vinci users, although the Nobel is a stand-alone printer that can pull a .STL file from a USB drive and turn it into an object without a computer. There was no mention of how – or if – this printer is locked down.

DWS Lab XFAB

You’ve seen the cheapest, now check out the most expensive. It’s the DWS Lab XFAB, an enormous and impressive machine that has incredible resolution, a huge build area, and when you take into account other resin printers, a price approaching insanity.

First, the price: $5000 officially, although I heard rumors of $6500 around the 3D printing tent. No, it’s not for sale yet – they’re still in beta testing. Compare that to the Formlabs Form 1+ at $3300, or the XYZPrinting Nobel at $1500, and you would expect this printer to be incredible. You would be right.

The minimum feature size of the XFAB is 80 microns, and can slice down to 10 microns. Compare that to the 300 micron feature size of the Form 1+ and Nobel, and even on paper, you can tell they really have something here. Looking at the sample prints, they do. These are simply the highest resolution 3D printed objects I’ve ever seen. The quality of the prints compares to the finest resin cast objects, machined plastic, or any other manufacturing process. If you’re looking for a printer for very, very high quality work, this is what you need.

Sharebot Voyager

Also on display – but not in the 3D printing booth, for some reason – was the Sharebot Voyager. Unlike all the printers described above, this is a DLP printer; instead of lasers and galvos, the Voyager uses an off-the-shelf 3D DLP projector to harden layers of resin.

Also on display – but not in the 3D printing booth, for some reason – was the Sharebot Voyager. Unlike all the printers described above, this is a DLP printer; instead of lasers and galvos, the Voyager uses an off-the-shelf 3D DLP projector to harden layers of resin.

Strangely, the Sharebot Voyager was stuck in either the Atmel or the Arduino.cc (the [Massimo] one) booth. The printing area is a bit small – 56x96x100mm, but the resolution – on paper, mind you – goes beyond what the most expensive laser and galvo printers can manage: 50 microns in the X and Y axes, 20 to 100 microns in the Z. Compare that figure to the XFAB’s 80 micron minimum feature size, and you begin to see the genius of using a DLP projector.

The Sharebot Voyager is fully controllable over the web thanks to a 1.5GHz quad core, 1GB RAM computer that I believe is running 32 bit Windows. Yes, the spec sheet said OS: 32 bit Windows.

There were no sample prints, no price, and no expected release date. It is, for all intents and purposes, vaporware. I’ve seen it, I’ve taken pictures of it, but I’ve done that for a lot of products that never made it to market.

The Problem With Resin Printers

Taking a gander over all the resin-based 3D printers, you start to pick up on a few common themes. All the software is proprietary, and there is no open source solution for either moving galvos, lasers, or displaying images on a DLP projector correctly to run a resin-based machine. Yes, you heard it here first: it’s the first time in history Open Source hardware folk are ahead of the Open Source software folk. Honestly, open source resin printer hosts is something that should have been done years ago.

This will change in just a few months. A scary, tattooed little bird told me there will soon be an open source solution to printing in resin by the Detroit Maker Faire. Then, finally, the deluge of resin.

3D Printering: Laser Cutting 3D Objects

3D printing can create just about any shape imaginable, but ask anyone who has babysat a printer for several hours, and they’ll tell you 3D printing’s biggest problem: it takes forever to produce a print. The HCI lab at Potsdam University has some up with a solution to this problem using the second most common tool found in a hackerspace. They’re using a laser cutter to speed up part production by a factor of twenty or more.

Instead of printing a 3D file directly, this system, Platener, breaks a model down into its component parts. These parts can then be laser cut out of acrylic or plywood, assembled, and iterated on much more quickly.

You might think laser-cut parts would only be good for flat surfaces, but with techniques like kerf bending, and stacking layer upon layer of material on top of each other, just about anything that can be produced with a 3D printer is also possible with Platener.

To test their theory that Platener is faster than 3D printing, the team behind Platener downloaded over two thousand objects from Thingiverse. The print time for these objects can be easily calculated for both traditional 3D printing and the Platener system, and it turns out Platener is more than 20 times faster than printing more than thirty percent of the time.

You can check out the team’s video presentation below, with links to a PDF and slides on the project’s site.

Thanks [Olivier] for the tip.

3D Printering: Induction Heating

Every filament-based 3D printer you’ll find today heats plastic with resistive heaters – either heater cartridges or big ‘ol power resistors. It’s efficient, but that will only get you so far. Given these heaters can suck down only so many Watts, they can only heat up so fast. That’s a problem, and if you’re trying to make a fast printer, it’s also a limitation.

Instead of dumping 12 or 24 VDC into a resistive heater, induction heaters passes high-frequency AC through a wire that’s inductively coupled to a core. It’s also very efficient, but it’s also very fast. No high-temperature insulation is required, and if it’s designed right, there’s less thermal mass. All great properties for fast heating of plastic.

A few years ago, [SB] over on the RepRap blog designed an induction heater for a Master’s project. The hot end was a normal brass nozzle attached to a mild steel sleeve. A laminated core was attached to the hot end, and an induction coil wrapped around the core. It worked, but there wasn’t any real progress for turning this into a proper nozzle and hot end. It was, after all, just a project.

Finally, after several years, people are squirting plastic out of an induction heated nozzle. [Z], or [Bulent Unalmis], posted a project to the RepRap forums where he is extruding plastic that has been heated with an induction heater. It’s a direct drive system, and mechanically, it’s a simpler system than the fancy hot ends we’re using now.

Electronically, it’s much more complex. While the electronics for a resistive heater are just a beefy power supply and a MOSFET, [Z] is using 160 kHz AC at 30 V. That’s a much more difficult circuit to stuff on a printer controller board.

This could be viewed as just a way of getting around the common 24V limitation of common controller boards; shove more power into a resistor, and it’s going to heat faster. This may not be the answer to hot ends that heat up quicker, but at the very least it’s a very neat project, and something we’d like to see more of.

You can see [Z]’s video demo of his inductive hot end below. Thanks [Matt] for the tip.