3D printing is all well and good for making low numbers of units, so long as they’re small enough to print in a reasonable time, but what if you want to go really big? Does a 35-hour print time sound like a fun time? Would it even make it that long? [Nathan] from Nathan Build Robots didn’t fancy the wait, so they embarked on a project to build a huge parallel 3D printer with four independent print heads. Well, kind of. Continue reading “Fast 3D Printing With A Polar, Four Quadrant Custom Machine”

It Turns Out, A PCB Makes A Nice Watch Dial

Printed circuit boards are typically only something you’d find in a digital watch. However, as [IndoorGeek] demonstrates, you can put them to wonderful use in a classical analog watch, too. They can make the perfect watch dial!

Here’s the thing. A printed circuit board is fundamentally some fiberglass coated in soldermask, some copper, maybe a layer of gold plating, and with some silk screen on top of that. As we’ve seen a million times, it’s possible to do all kinds of artistic things with PCBs; a watch dial seems almost obvious in retrospect!

[IndoorGeek] steps through using Altium Designer and AutoCAD to layout the watch face. The guide also covers the assembly of the watch face into an actual wrist watch, including the delicate placement of the movement and hands. They note that there are also opportunities to go further—such as introducing LEDs into the watch face given that it is a PCB, after all!

It’s a creative way to make a hardy and accurate watch face, and we’re surprised we haven’t seen more of this sort of thing before. That’s not to say we haven’t seen other kinds of watch hacks, though; for those, there have been many. Video after the break.

Continue reading “It Turns Out, A PCB Makes A Nice Watch Dial”

Experimenting With Interference On Thin Layers

[Stoppi] has taken on a fascinating project involving the interference of thin layers, a phenomenon often observed in everyday life but rarely explored in such depth. This project delves into the principles of interference, particularly focusing on how light waves interact with very thin films, like those seen in soap bubbles or oil slicks. The post is in German, but you can easily translate it using online tools.

Interference occurs when waves overlap, either reinforcing each other (constructive interference) or canceling each other out (destructive interference). In this project, [Stoppi] specifically examines how light behaves when passing through thin layers of air trapped between semi-transparent mirrors. When light waves reflect off these mirrors, the difference in path length leads to interference patterns that depend on the layer’s thickness and the wavelength of the light.

To visualize this, [Stoppi] used an interferometer made from semi-transparent mirrors and illuminated it with a bulb to ensure a continuous spectrum of light. By analyzing the transmitted light spectrum with a homemade spectrometer, he observed clear peaks corresponding to specific wavelengths that could pass through the interferometer. These experimental results align well with theoretical predictions, confirming the effectiveness of the setup.

If you like pretty patterns, soap bubbles are definitely good for several experiments. Don’t forget: pictures or it didn’t happen.

Continue reading “Experimenting With Interference On Thin Layers”

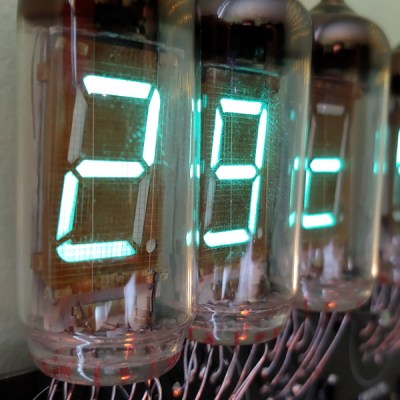

Supercon 2024: Show Off Your Unique Display Tech

If there’s a constant in the world of electronics, it’s change. Advancements and breakthroughs mean that what was once state-of-the-art all too soon finds itself collecting dust. But there are exceptions. Perhaps because they’re so much more visible to us than other types of components, many styles of displays have managed to carve out their own niche and stick around. Even for the display types that we no longer see used in consumer hardware, their unique aesthetic qualities often live on in media, art, and design.

This year, to coincide with Hackaday Supercon, the folks at Supplyframe’s DesignLab want to pay tribute to display technology past and present with a special exhibit — and they need your help to make it possible. If you have a display you’d like to show off, fill out this form and tell them what you’ve got. Just be sure to do it by September 16th.

This year, to coincide with Hackaday Supercon, the folks at Supplyframe’s DesignLab want to pay tribute to display technology past and present with a special exhibit — and they need your help to make it possible. If you have a display you’d like to show off, fill out this form and tell them what you’ve got. Just be sure to do it by September 16th.

For the larger specimens, it would be ideal if you’re somewhat local to Southern California, but otherwise, they’re looking for submissions from all over the world. The exhibit will open on the first day of Supercon and run throughout November.

Don’t worry. They’re only looking to raid your parts bin temporarily. Any hardware sent in to be part of the exhibit will be considered on loan, and they’ll make sure it gets back to where it belongs by January 31st, 2025. The goal is to show the displays on and operational, so in most cases, that’s going to mean sending over a complete device. But if it’s possible to isolate the display itself and still demonstrate what it would look like in operation, sending along just the bare display is an option. Continue reading “Supercon 2024: Show Off Your Unique Display Tech”

Keebin’ With Kristina: The One With The Folding Typewriter

Have you built yourself a macro pad yet? They’re all sorts of programmable fun, whether you game, stream, or just plain work, and there are tons of ideas out there.

This baby runs on an ATmega32U4, which known for its Human Interface Device (HID) capabilities. [CiferTech] went with my own personal favorite, blue switches, but of course, the choice is yours.

There are not one but two linear potentiometers for volume, and these are integrated with WS2812 LEDs to show where you are, loudness-wise. For everything else, there’s an SSD1306 OLED display.

But that’s not all — there’s a secondary microcontroller, an ESP8266-07 module that in the current build serves as a packet monitor. There’s also a rotary encoder for navigating menus and such. Make it yours, and show us!

Continue reading “Keebin’ With Kristina: The One With The Folding Typewriter”

Backlight Switch For A Better Multimeter

Frustrated by his Aldi multimeter’s backlight turning off after just 15 seconds, [Steg Steg] took matters into his own hands. His solution? He added a manual toggle switch to control the backlight, allowing it to stay on as long as needed. He began by disassembling the multimeter—removing the outer bumper and a few screws—to access the backlight, labeled “BL.” He identified the voltage regulator outputting 2.8 V, desoldered the red wire, and extended it to install the switch.

On his first try, he successfully drilled a spot for the SPST switch. To fit the switch into the multimeter’s rubber bumper, he used a circular punch, although his second hole wasn’t as clean as the first. Despite this minor setback, the modification worked perfectly, giving him complete control over his multimeter’s backlight without the original 15-second timeout.

Everything You Wanted To Know About Early Macintosh Floppies

Using a disk drive today is trivial. But back “in the day,” it was fairly complex both because the drives were simple and the CPUs were not powerful by today’s standards. [Thomas] has been working on a 68000 Mac emulator and found that low-level floppy information was scattered in different places. So he’s gathered it all for us in one place.

Low-level disk access has a lot of subtle details. For example, the Mac calibrates its speed control on boot. If your emulated drive just sets the correct speed and doesn’t respond to changes during calibration, the system will detect that as an error. Other details about spinning disks include the fact that inner tracks are shorter than outer track and may require denser recordings. Laying out sectors can also be tricky since you will lose performance if you, for example, read sector one and then miss sector two and have to wait for it to come back around. Disk sectors are often staggered for this reason.

Adding to the complexity is the controller — the IWM or Integrated Woz Machine — which has an odd scheme for memory mapping I/O. You should only access the odd bytes of the memory-mapped I/O. The details are all in the post.

In a way, we don’t miss these days, but in other ways, we do. It wasn’t that long ago that floppies were king. Now it is a race to preserve the data on them while you still can.