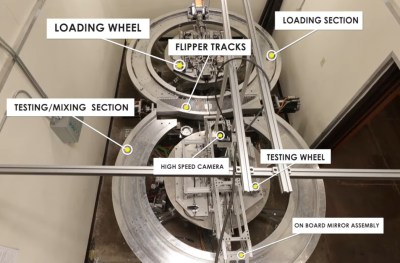

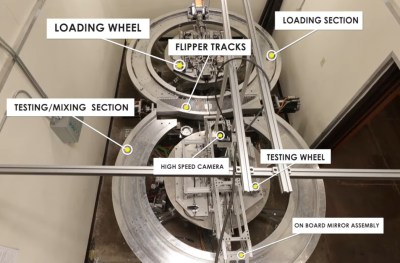

Sometimes a paper in a scientific journal pops up that makes you do a triple-take, case in point being a recent paper by [Aren Boyaci] and [Arindam Banerjee] in Physical Review E titled “Transition to plastic regime for Rayleigh-Taylor instability in soft solids”. The title doesn’t quite do their methodology justice — as the paper describes zipping a container filled with mayonnaise along a figure-eight track to look at the surface transitions. With the paper paywalled and no preprint available, we have to mostly rely the Lehigh University press releases pertaining to the original 2019 paper and this follow-up 2024 one.

Rayleigh-Taylor instability (RTI) is an instability of an interface between two fluids of different densities when the less dense fluid acts up on the more dense fluid. An example of this is water suspended above oil, as well as the expanding mushroom cloud during a explosion or eruption. It also plays a major role in plasma physics, especially as it pertains to nuclear fusion. In the case of inertial confinement fusion (ICF) the rapidly laser-heated pellet of deuterium-tritium fuel will expand, with the boundary interface with the expanding D-T fuel subject to RTI, negatively affecting the ignition efficiency and fusion rate. A simulation of this can be found in a January 2024 research paper by [Y. Y. Lei] et al.

As a fairly chaotic process, RTI is hard to simulate, making a physical model a more ideal research subject. Mayonnaise is definitely among the whackiest ideas here, with other researchers like [Samar Alqatari] et al. as published in Science Advances opting to use a Hele-Shaw cell with dyed glycerol-water mixtures for a less messy and mechanically convoluted experimental contraption.

As a fairly chaotic process, RTI is hard to simulate, making a physical model a more ideal research subject. Mayonnaise is definitely among the whackiest ideas here, with other researchers like [Samar Alqatari] et al. as published in Science Advances opting to use a Hele-Shaw cell with dyed glycerol-water mixtures for a less messy and mechanically convoluted experimental contraption.

What’s notable here is that the Lehigh University studies were funded by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), which explains the focus on ICF, as the National Ignition Facility (NIF) is based there.

This also makes the breathless hype about ‘mayo enabling fusion power’ somewhat silly, as ICF is even less likely to lead to net power production, far behind even Z-pinch fusion. That said, a better understanding of RTI is always welcome, even if one has to question the practical benefit of studying it in a container of mayonnaise.