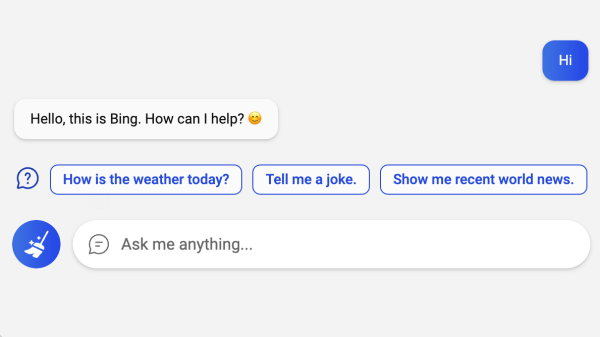

Interested in AI, but sick of using everything in a browser? Miss clicking on a good old desktop icon to open a local bit of software? In that case, BingGPT could be just the thing for you.

It’s nothing too crazy—just a desktop application that gives you access to Bing’s AI-powered chatbot. It’s available on a range of platforms, from Windows, to Apple, and Linux, and binaries are available for Intel, Apple Silicon, and ARM processors.

Using BingGPT is simple. Sign in with your Microsoft account, and away you go. There’s no need to use Microsoft Edge or any ugly browser plugins, and you can export your conversations to Markdown, PNG, and PDF for sharing beyond the program. It’s also complete with a range of keyboard shortcuts to speed your interaction with the large language model when it gets off track. There’s also the Compose button which can actually go ahead and write stuff for you.

Fundamentally, all the cool stuff is still coming in via the web, but it’s nice to be able to use Bing’s chatbot without having to succumb to the horrors of a Microsoft browser. It’s interesting to see how large language models are becoming an all-pervasive tool of late. If you’re building your own nifty projects in this area, don’t hesitate to let us know!