At a far flung, wind blown, outpost of Hackaday, we were watching a spy film with a bottle of suitably cheap Russian vodka when suddenly a blonde triple agent presented a fascinating looking gadget to a lock and proceeded to unpick it automatically. We all know very well that we should not believe everything we see on TV, but this one stuck.

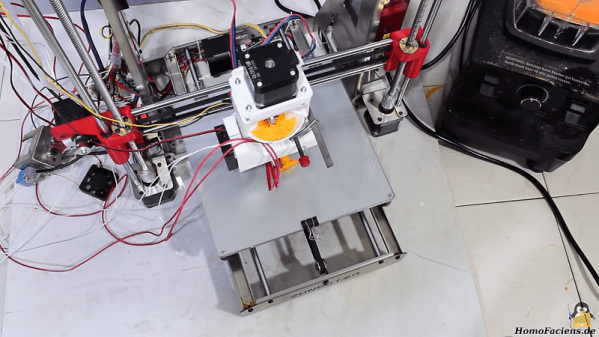

Now, for us at least, fantasy became a reality as [Peterthinks] makes public his 3D printed lock picker – perfect for the budding CIA agent. Of course, the Russians have probably been using these kind of gadgets for much longer and their YouTube videos are much better, but to build one’s own machine takes it one step to the left of center.

Now, for us at least, fantasy became a reality as [Peterthinks] makes public his 3D printed lock picker – perfect for the budding CIA agent. Of course, the Russians have probably been using these kind of gadgets for much longer and their YouTube videos are much better, but to build one’s own machine takes it one step to the left of center.

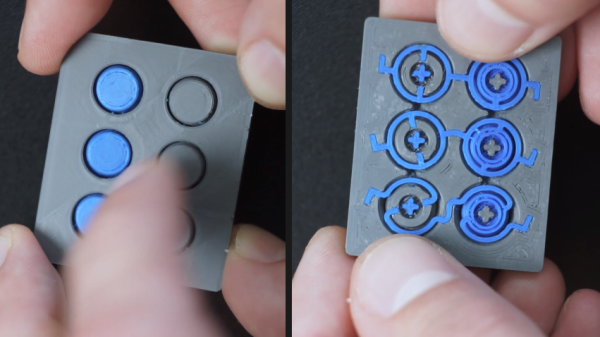

The device works by manually flicking the spring (rubber band) loaded side switch which then toggles the picking tang up and down whilst simultaneously using another tang to gently prime the opening rotator.

The device works by manually flicking the spring (rubber band) loaded side switch which then toggles the picking tang up and down whilst simultaneously using another tang to gently prime the opening rotator.

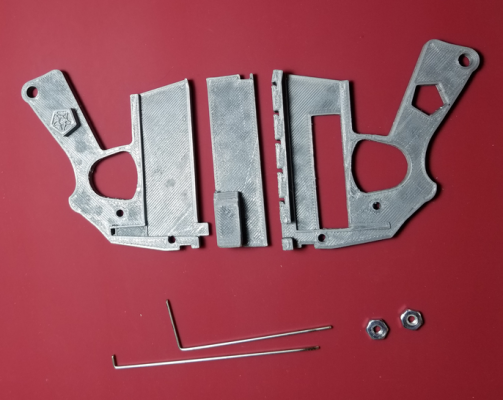

The size of the device makes it perfect to carry around in a back pocket, waiting for the chance to become a hero in the local supermarket car park when somebody inevitably locks their keys in their car, or even use it in your day job as a secret agent. Just make sure you have your CIA, MI6 or KGB credentials to hand in case you get searched by the cops or they might think you were just a casual burglar. Diplomatic immunity, or a ‘license to pick’ would also be useful, if you can get one.

As mentioned earlier, [Peter’s] video is not the best one to explain lock picking, but he definitely gets the prize for stealth. His videos are below the break.

In the meantime, all we need now are some 3D printed tangs.

Continue reading “3D Printed Snap Gun For Automatic Lock Picking”