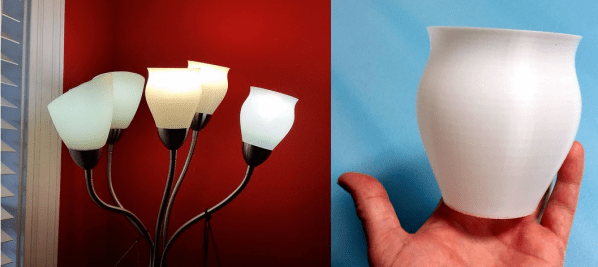

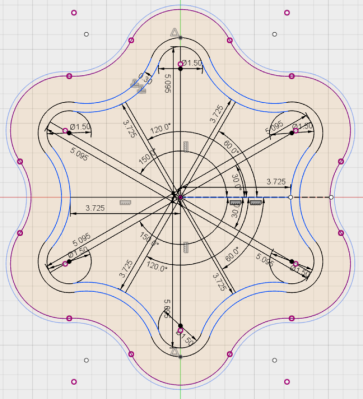

We all have that one possession—maybe more than one—that we’ve had forever and refuse to let go of, even though it has seen better days. When that something is a useful appliance, it can be heartbreaking to watch it deteriorate. For [Elmojo], that thing is a 10+ year old Medusa-style floor lamp. It still looks and works great, but the plastic shades are crumbling. The good news: [Elmojo] has a 3D printer.

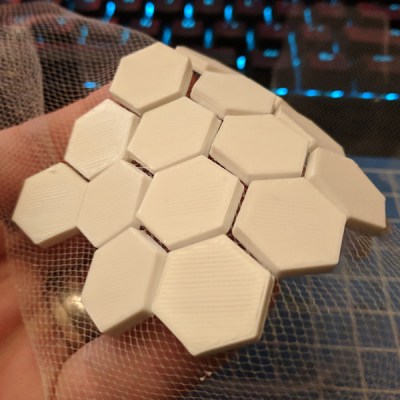

Here’s where things get exciting. Not only did [Elmojo] have a pretty good chance of making new shades that would work, he had a chance to change the design, and he did. He could have made ’em look like those twisted or low-poly vases that everybody loves to print. And he still could do that. See, that’s one of the best things about 3D printers.  Not only can you rejuvenate beloved objects, you can do it your way. Experiment. You could print out a whole collection and change the shades once a week. Different shapes, different colors. Glow-in-the-dark shades!

Not only can you rejuvenate beloved objects, you can do it your way. Experiment. You could print out a whole collection and change the shades once a week. Different shapes, different colors. Glow-in-the-dark shades!

[Elmojo] printed the new shades with white BAMTack! (emphasis theirs), and they have been going strong for a while now. The two on the left are the original shades, and the three on the right were printed.

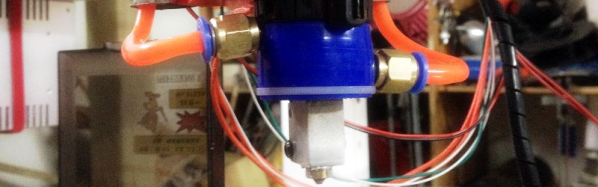

There’s still plenty of time to enter our Repairs You Can Print contest, which runs until high noon Pacific time on February 20th. Don’t forget—we’re giving away TWO Prusa i3 Mk3s plus the multi-material upgrade—one to the best student entry and the other to the best entry from an organization. Isn’t there something you’ve been meaning to fix?