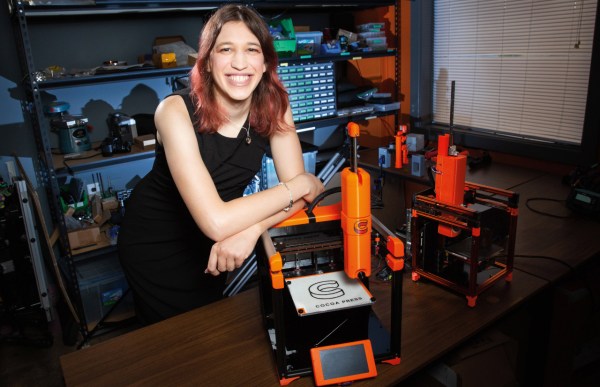

In the bright sunshine of a warm spring afternoon at Delft Maker Faire, were a row of 3D printers converted with paste extruders. They were the work of [Nedji Yusufova], and though while were being shown printing with biodegradable pastes made from waste materials, we were also interested in their potential to print using edible media.

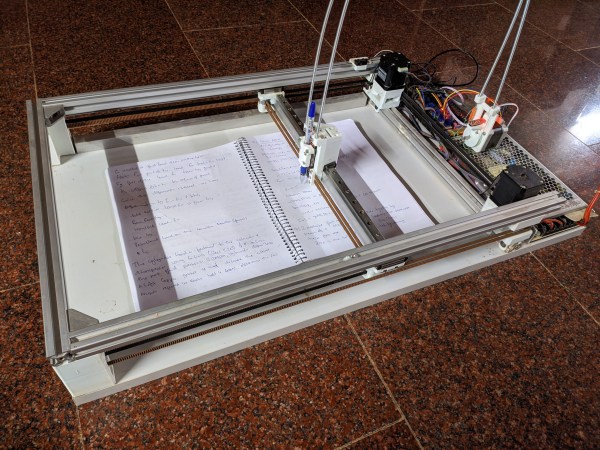

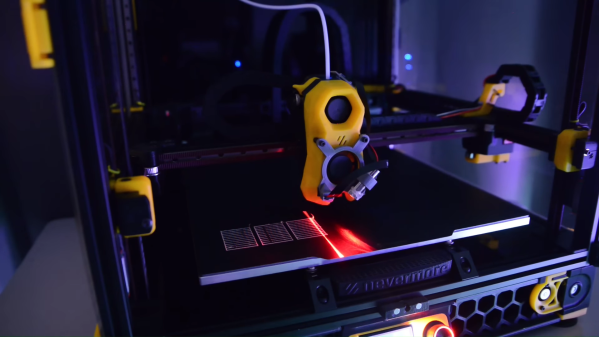

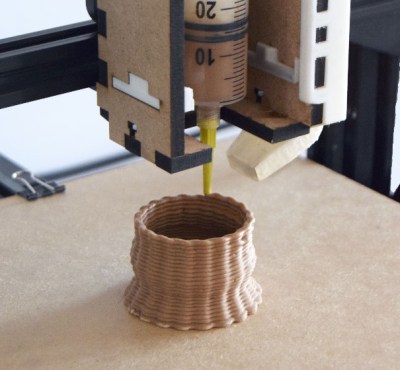

The extruder follows a path set by similar ones we’ve seen before in that it uses a disposable syringe at its heart, this time in a laser-cut ply enclosure and a lead screw driven by a stepper motor. It’s part of a kit suitable for run-of-the-mill FDM printers that’s available for sale if you have the extra cash, but happily they’ve also made all the files available.

The extruder follows a path set by similar ones we’ve seen before in that it uses a disposable syringe at its heart, this time in a laser-cut ply enclosure and a lead screw driven by a stepper motor. It’s part of a kit suitable for run-of-the-mill FDM printers that’s available for sale if you have the extra cash, but happily they’ve also made all the files available.

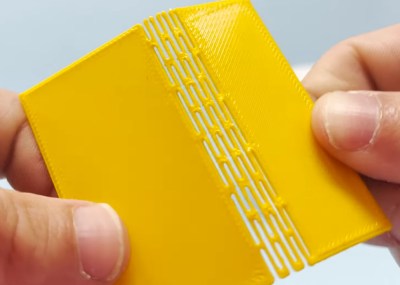

We’ve seen quite a few syringe extruders and at least one food printer, so there’s nothing particularly new about this one. What it does give you is a relatively straightforward build and a ready integration with some mass market printers you might be familiar with. Perhaps the most interesting part of this project isn’t even the extruder itself but the materials, after all having a paste extruder gives you the opportunity to experiment with new recipes. We like it.