Saving money is inherently no fun until the time comes that you get to spend it on something awesome. Wouldn’t you be more likely to drop your coins into a piggy bank if there was a chance for an immediate payout that might exceed the amount you put in? We know we would. And the best part is, if you put such a piggy bank slot machine out in the open where your friends and neighbors can play with it, you’ll probably make even more money. As they say, the house always wins.

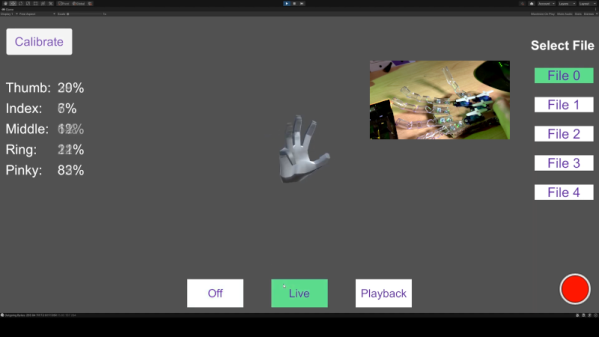

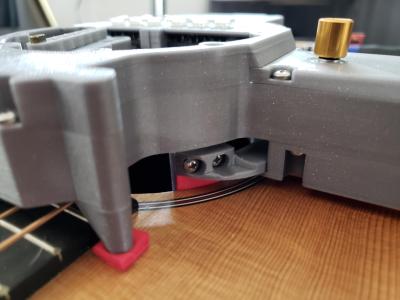

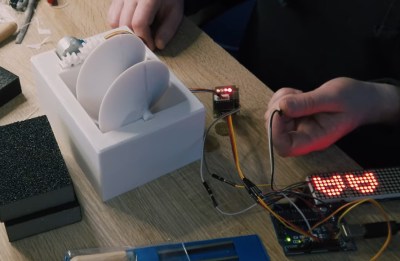

Drop a coin in the slot and it passes through a pair of wires that act as a simple switch to start the reels spinning. Inside is an Arduino Uno and a giant printed screw feeder that’s driven by a small stepper motor and a pair of printed gears. The reels have been modernized and the display is made of four individual LED matrices that appear as a single unit thanks to some smoky adhesive film.

Drop a coin in the slot and it passes through a pair of wires that act as a simple switch to start the reels spinning. Inside is an Arduino Uno and a giant printed screw feeder that’s driven by a small stepper motor and a pair of printed gears. The reels have been modernized and the display is made of four individual LED matrices that appear as a single unit thanks to some smoky adhesive film.

This beautiful little machine took a solid week of 3D printing, which includes 32 hours wasted on a huge piece that failed twice. [Max 3D Design] tried rotating the model 180° in the slicer and thankfully, that solved the problem. Then it was on to countless hours of sanding, smoothing with body filler, priming, and painting to make it look fantastic.

If you want to make your own, all the files are up on Thingiverse. The code isn’t shown, but we know for a fact that Arduino slot machine code is out there already. Check out the build and demo video after the break.

As much as we like this build’s simplicity, it would be more slot machine-like if there was a handle to pull. Turns out you can print those, too.

Continue reading “Piggy Bank Slot Machine Puts A Spin On Saving”