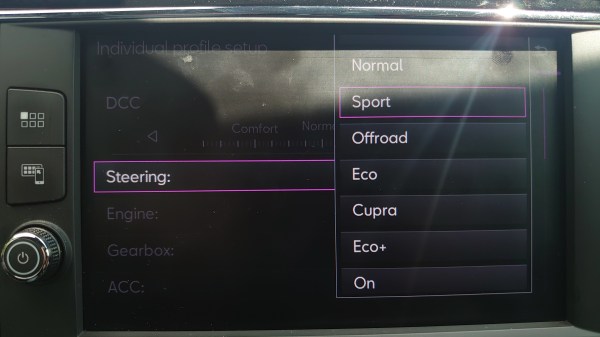

Just like mobile phones of yesteryear, modern cars have profiles. They aren’t responsible for the sounds your car produces, however, as much as they change how your car behaves – for instance, they can make your engine more aggressive or tweak your steering resistance. On MQB platform cars, the “Gateway” module is responsible for these, and it’s traditionally been a black box with a few user-exposed profiles – not as much anymore, thanks to the work of [Jille]. They own a Volkswagen hybrid car, and had fun changing driving modes on it – so naturally, they decided to reverse-engineer the configuration files responsible.

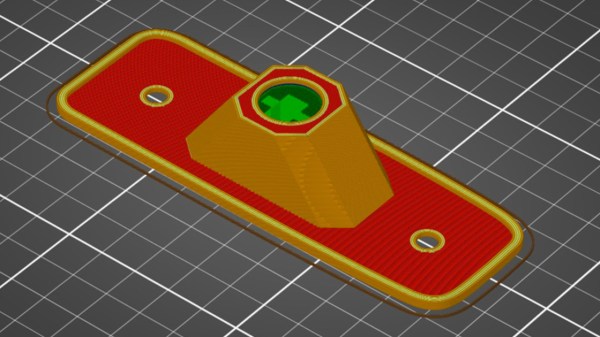

Now, after two years of experimentation, tweaking values and observing changes, there’s quite some sense made of the configuration binaries. You can currently edit these binaries, also referred to as datasets, in a hex editor – there’s profiles for the 010 hex editor that make sense of the data you load, and explanation of the checksums involved. With this, you are no longer limited by profiles the manufacturer composed – if a slightly different driving combination of parameters makes more sense to you, you can recombine them and have your own profile, unlock modes that the manufacturer decided to lock out for non-premium cars, and even fix some glaring oversights in factory modes.

This is pretty empowering, and far from ECU modifications that introduce way more fundamental changes to how your car operates – the parameters being changed are within the range of what the manufacturer has implemented. The smarter our cars become, the more there is for us hackers to tweak, and even in a head unit, you can find things to meaningfully improve given some reverse-engineering smarts.