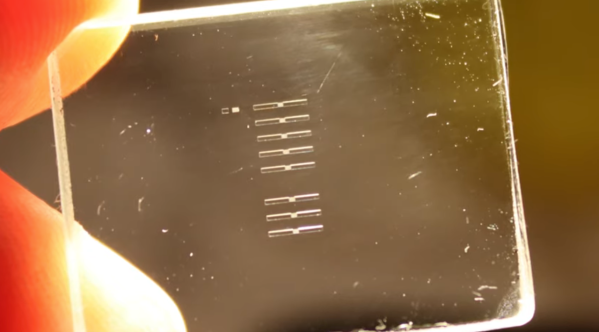

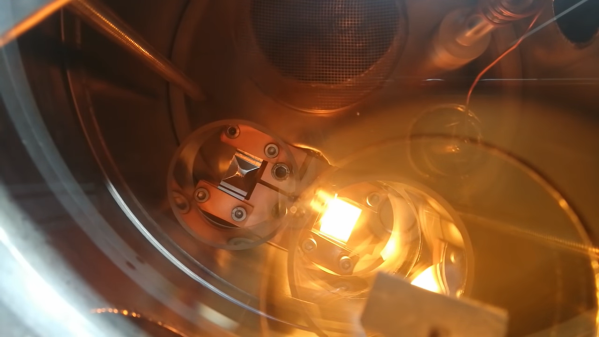

The unspoken promise of new technologies is that they will advance and enhance our picture of the world — that goes double for the ones that are specifically designed to let us look closer at the physical world than we’ve ever been able to before. One such advancement was the invention of X-ray crystallography that let scientists peer into the spatial arrangements of atoms within a molecule. Kathleen Lonsdale got in on the ground floor of X-ray crystallography soon after its discovery in the early 20th century, and used it to prove conclusively that the benzene molecule is a flat hexagon of six carbon atoms, ending a decades-long scientific dispute once and for all.

Benzene is an organic chemical compound in the form of a colorless, flammable liquid. It has many uses as an additive in gasoline, and it is used to make plastics and synthetic rubber. It’s also a good solvent. Although the formula for benzene had been known for a long time, the dimensions and atomic structure remained a mystery for more than sixty years.

Kathleen Lonsdale was a crystallography pioneer and developed several techniques to study crystal structures using X-rays. She was brilliant, but she was also humble, hard-working, and adaptable, particularly as she managed three young children and a budding chemistry career. At the outbreak of World War II, she spent a month in jail for reasons related to her staunch pacifism, and later worked toward prison reform, visiting women’s prisons habitually.

After the war, Kathleen traveled the world to support movements that promote peace and was often asked to speak on science, religion, and the role of women in science. She received many honors in her lifetime, and became a Dame of the British Empire in 1956. Before all of that, she honored organic chemistry with her contributions.

Continue reading “Kathleen Lonsdale Saw Through The Structure Of Benzene”