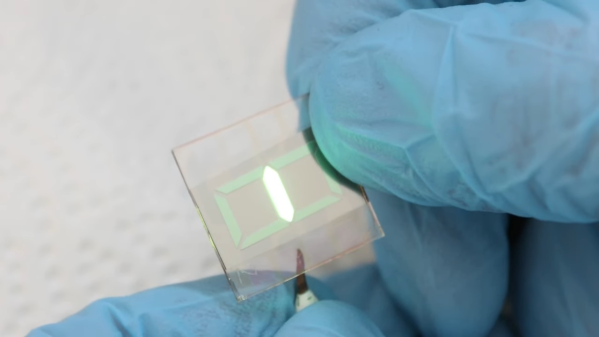

Historically, coffee has needed two things to grow successfully — a decent altitude and a warm climate. Now, a group of scientists from the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland have managed to grow coffee in a lab. They started by culturing coffee plant cells, and then planted them in bioreactors full of nutrient-rich growing medium. But they didn’t grow plants. Instead of green beans inside coffee cherries, the result is a whitish powdered biomass that resembles pure caffeine. Then the scientists roasted the powder as you would beans, and report that it smells and tastes just like regular coffee.

There are plenty of problems percolating with the coffee industry that make this an attractive alternative — mostly worker exploitation, unsustainable farming methods, and land rights issues. And the Bean Belt, which stretches from Ethiopia to South America to Southeast Asia is getting too hot. On top of all that, coffee production is driving deforestation in Vietnam and elsewhere, although coffee could help the forests regenerate more quickly.

Coffee purists shouldn’t be dismayed, because variety is still possible using varying cell cultures to dial in the caffeine level and the flavors. We’ll drink to that.

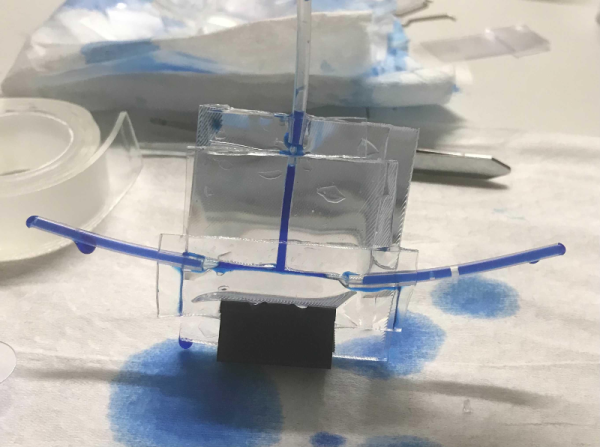

Another thing in the industry that’s a real grind is coffee cupping, but spectroscopy could soon help determine bean quality.