Today, the US Department of Transportation announced that unmanned aerial systems (UAS) will require registration in the future.

The announcement is not that UAS, quadcopters, or drones would be required to be registered immediately. This announcement is merely that a task force of representatives from the UAS industry, drone manufacturers, and manned aviation industries would provide recommendations to the Department of Transportation for what types of aircraft would require registration. The task force is expected to develop these recommendations and deliver a report by November 20.

A Short History of FAA Model Aircraft Regulation

Introduced in 1981, AC 91-57 was the model aircraft operating standards for more than 30 years. This standard suggested that model pilots not fly higher than 400 feet, and to notify a flight service station or control tower when flying within three miles of an airport.

The FAA Modernization And Reform Act Of 2012 (PDF) required the FAA to create a set of rules for unmanned aerial systems, however the FAA is expressly forbidden from, ‘promulgating any rule or regulation regarding model aircraft.’ The key term being, ‘model aircraft’. This term was defined by the FAA as being, “an unmanned aircraft that is capable of sustained flight in the atmosphere; flown within visual line of sight of the person operating the aircraft; and flown for hobby or recreational purposes.” Anything outside of this definition was an unmanned aerial system, and subject to FAA regulations.

While this definition of model aircraft would have been fine for the 1980s, technology has advanced since then. FPV flying, or putting a camera and video transmitter on a quadcopter, is an extraordinarily popular hobby now, and because it is not ‘line of sight’, it is outside the definition of ‘model aircraft’.

This interpretation has not seen a great deal of countenance from the model aircraft community; FPV flying is seen as a legitimate hobby and even a sport. The entire domain of model aircraft aviation is expanding, and the hobby has never been as popular as it is now.

The Safety of Model Aviation

The issue of drone regulation focuses nearly entirely on the safety of airways in the United States; model aviators flying within five miles of an airport must ask the airport or control tower for permission to fly. To that end, the FAA created the B4UFLY app that takes the trouble out of reading sectional charts and checking up on the latest NOTAMs and TFRs.

However, the FAA is increasingly concerned with drones, multicopters, and model aircraft. In a report issued last summer, the FAA cited a marked increase in the number of ‘close calls’ between manned aircraft and model aircraft. The Academy of Model Aeronautics went over this data and found a different story: only 3.5% of sightings were ‘close calls’ or ‘near misses’. The FAA data is questionable – the reports cited include a drone flying at 51,000 feet over Washington DC. Not only is this higher than any civilian passenger aircraft capable of flying, the ability for any civilian remote-controlled aircraft to operate at this altitude is questionable at best.

Nevertheless, the requirement for registration has been greatly influenced by the perceived concerns of regulators for mid-air collisions.

What exactly will require registration?

The group of industry representatives responsible for delivering the recommendations to the Department of Transportation will take into account what aircraft should be exempt from registration due to a low safety risk. Most likely, small toy quadcopters will be exempt from registration; it’s difficult to fly a small Cheerson quadcopter outside anyway. Whether this will affect larger quadcopters and drones such as the DJI Phantom, or 250 class FPV racing quadcopters remains to be seen.

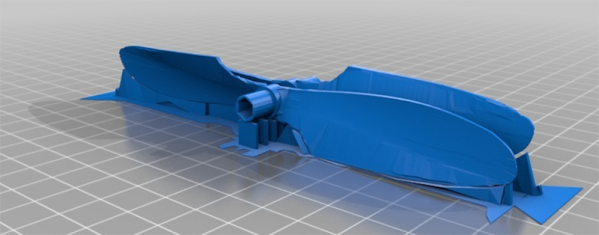

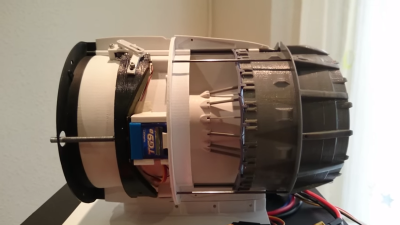

What sets this apart from other jet models is the working reverse thrust system. [Harcoreta] painstakingly modeled the cascade reverse thrust setup on the 787/GEnx-1B combo. He then engineered a way to make it actually work using radio controlled plane components. Two servos drive threaded rods. The rods move the rear engine cowling, exposing the reverse thrust ducts. The servos also drive a complex series of linkages. These linkages actuate cascade vanes which close off the fan exhaust. The air driven by the fan has nowhere to go but out the reverse thrust ducts. [Harcoreta’s] videos do a much better job of explaining how all the parts work together.

What sets this apart from other jet models is the working reverse thrust system. [Harcoreta] painstakingly modeled the cascade reverse thrust setup on the 787/GEnx-1B combo. He then engineered a way to make it actually work using radio controlled plane components. Two servos drive threaded rods. The rods move the rear engine cowling, exposing the reverse thrust ducts. The servos also drive a complex series of linkages. These linkages actuate cascade vanes which close off the fan exhaust. The air driven by the fan has nowhere to go but out the reverse thrust ducts. [Harcoreta’s] videos do a much better job of explaining how all the parts work together.