With the advent of cheap software defined radios made popular by the RTL-SDR project a few years back, satellite communications are now within the budget of even the most modest hacker. For $20 USD you can get a USB SDR module that is more than capable of receiving signals from any number of geosynchronous satellites, but you’ll need something a little more robust than rabbit ears to pick up a signal broadcast from over 22,000 miles away.

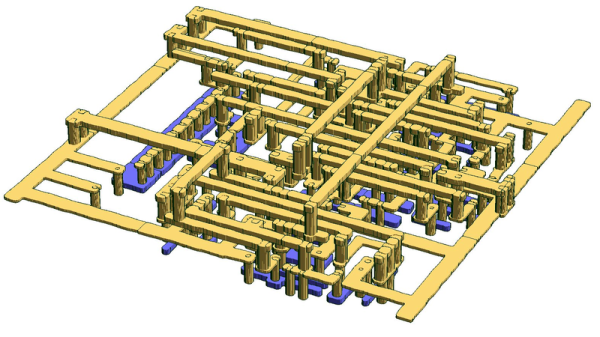

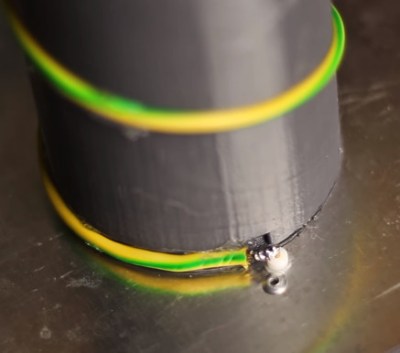

Building a satellite-capable antenna isn’t necessarily difficult, but does involve a fair bit of arcane black magic and mathematics to do properly; something that can scare away those new to the hobby. But by using a 3D printed mandrel, [Tysonpower] has come up with a feed you can build and mount on a standard dish without having to take a crash course in antenna theory. [Tysonpower] reports the feed has a center frequency 1550 MHz, and works well for reception of Inmarsat, AERO and HRPT signals.

Building a satellite-capable antenna isn’t necessarily difficult, but does involve a fair bit of arcane black magic and mathematics to do properly; something that can scare away those new to the hobby. But by using a 3D printed mandrel, [Tysonpower] has come up with a feed you can build and mount on a standard dish without having to take a crash course in antenna theory. [Tysonpower] reports the feed has a center frequency 1550 MHz, and works well for reception of Inmarsat, AERO and HRPT signals.

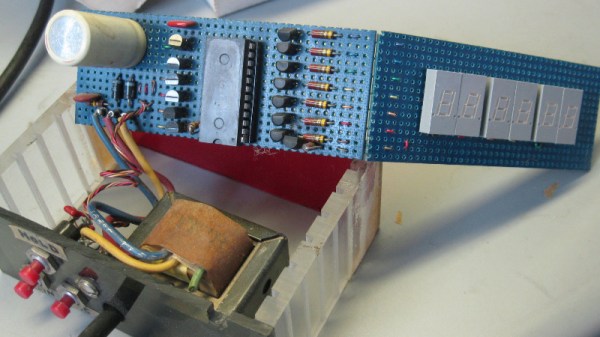

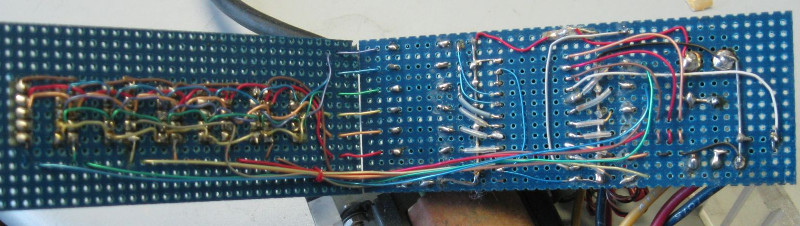

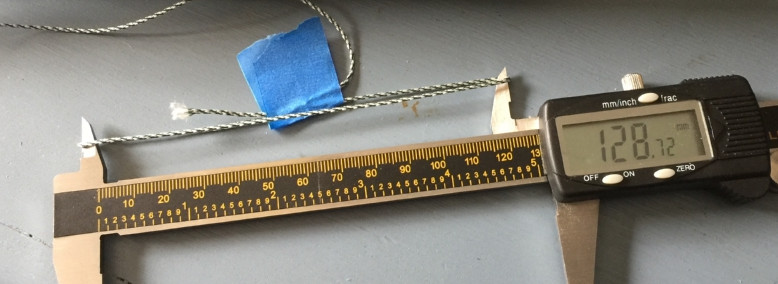

The channel in the 3D printed core of the feed ensures that the inserted wire is of the correct length and in the perfect position for optimal reception. All you need to do is print the core, wrap it with wire, and then solder the end to a connector on a ground-plane that’s nothing more than a sheet of aluminum. [Tysonpower] was even kind enough to model up a mount that will allow you to bolt this feed to a standard satellite dish.

We’ve previously covered using RTL-SDR to receive Inmarsat transmissions, and hardware for the Outernet project, both of which would be great applications for an antenna like this.