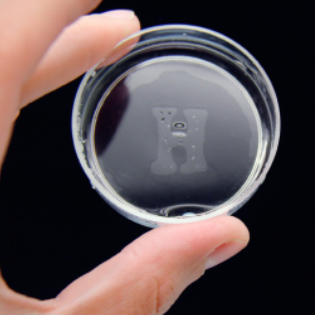

Here’s a short research paper from 2013 that explains how to create “hydroglyphics”, or writing with selecting surface wetting. In it, an apparently normal-looking petri dish is treated so as to reveal a message when wetted with water vapor. The contrast between hydrophobic and hydrophilic surfaces, which is not visible to the naked eye, becomes visible when misted with water. All it took was a mask, and a little treatment with a modified Tesla coil.

Plastics tend to be hydrophobic, meaning their surface repels water. These plastics also tend to be non-receptive to things like inks and adhesives. However, there is an industrial process called corona treatment (invented by Verner Eisby in 1951) that changes the surface energy of materials like plastics, rendering them more receptive to inks, coatings, and adhesives. Eisby’s company Vetaphone still exists today, and has a page describing the process.

Plastics tend to be hydrophobic, meaning their surface repels water. These plastics also tend to be non-receptive to things like inks and adhesives. However, there is an industrial process called corona treatment (invented by Verner Eisby in 1951) that changes the surface energy of materials like plastics, rendering them more receptive to inks, coatings, and adhesives. Eisby’s company Vetaphone still exists today, and has a page describing the process.

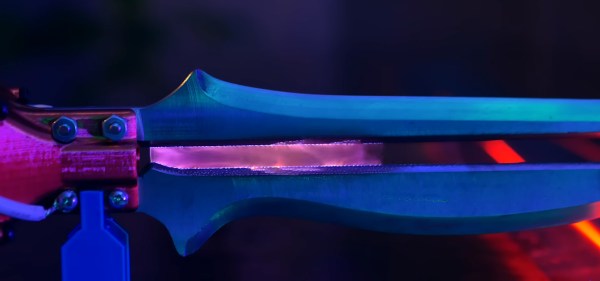

What’s this got to do with the petri dishes and their secret messages? The process is essentially the same. By using a Tesla coil modified with a metal wire mesh, the surface of the petri dish is exposed to the coil’s discharge, altering its surface energy and rendering it hydrophilic. By selectively blocking the discharge with a nonconductive mask made from a foam sticker, the masked area remains hydrophobic. Mist the surface with water, and the design becomes visible.

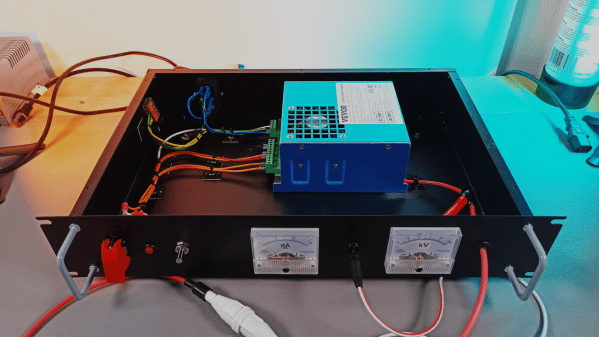

The effects of corona treatment decay over time, but we think this is exactly the sort of thing that is worth keeping in mind just in case it ever comes in useful. Compact Tesla coils are fairly easy to get a hold of nowadays, but it’s also possible to make your own.

![The nearly final measurement by [Double M Innovations].](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/hv_transmission_line_energy_harvesting_final_count.jpg?w=400)