The Mac Mini has been roughly the same size and shape for 12 years, as the current design was released in June 2010. However, despite being the same general form factor, the internals has shrunk over the years. [Snazzy Labs] took advantage of this to make a miniaturized Mac Mini.

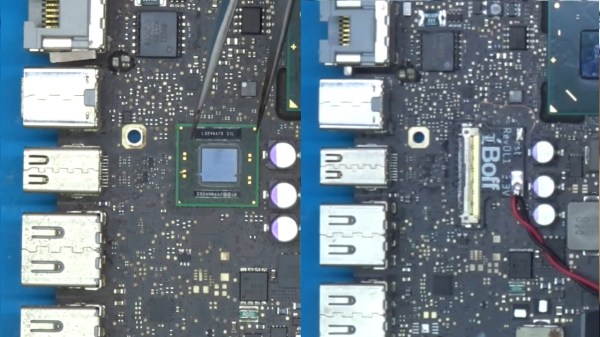

With a donor Mac in hand, they cracked it open and found an oversized power supply, a diminutive logic board, and a good bit of space. Unfortunately, the logic board attaches to a wide IO shield. He removed that, and the fan attached to the heatsink (checking to ensure it still booted). Relocating the WiFi antennas was the trickiest part of the whole build. Given that he wanted to shrink the power supply and the Mac Mini accepts just 12 volts, he devised a clever solution to use MagSafe as a connector. However, Magsafe negotiates over a complex protocol when attached. So, rather than smarten his port up, he dumbed the charger down by replacing it with a Microsoft Surface power supply spliced into the MagSafe connector.

With his mini Mac Mini board ready to go, he began designing a case to fit what was now a single-board computer. A fan of the channel offered a design reminiscent of the 2019 Mac Pro. Unfortunately, FDM printing struggled with the cheese-grater pattern, so [Snazzy Labs] printed it in resin with some mica powder. As a result, the mini mini looks fantastic while taking up just 28% of the volume of the original.

They’ve posted the STL files online with detailed instructions and a parts list if you want to recreate it at home. Perhaps with the smaller motherboard, it might be worth revisiting the Mac Mini inside a PowerBook hack from a few years ago. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Mac Mini Mini”

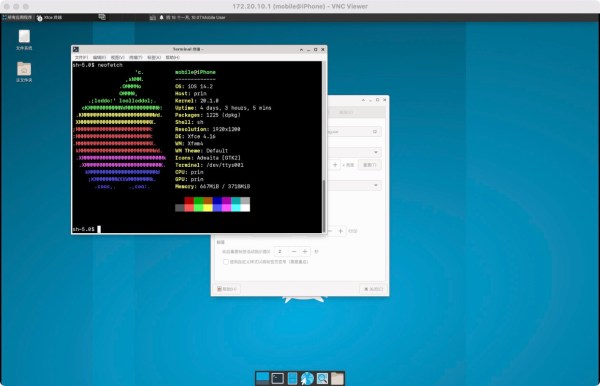

Unfortunately, it does require a more modern Mac to act as an access point into the wider iMessage network. The modern Mac sets up a GraphQL database that can be accessed. Then a serial cable connects your “retro daily driver” to a translation layer that converts the serial commands into GraphQL commands. This could be something simple and network-connected like an ESP32 or a program running on your iMessage Mac. [CamHenlin] has a second Mac mini in his demo, seen above.

Unfortunately, it does require a more modern Mac to act as an access point into the wider iMessage network. The modern Mac sets up a GraphQL database that can be accessed. Then a serial cable connects your “retro daily driver” to a translation layer that converts the serial commands into GraphQL commands. This could be something simple and network-connected like an ESP32 or a program running on your iMessage Mac. [CamHenlin] has a second Mac mini in his demo, seen above.