The future of tiny electronics is wearables, it seems, with companies coming out with tiny devices that are able to check your pulse, blood pressure, and temperature while relaying this data back to your phone over a Bluetooth connection. Intel has the Curie module, a small System on Chip (SoC) meant for wearables, and the STM32 inside the Fitbit is one of the smallest ARM microcontrollers you’ll ever find. Now there’s a new part available that’s smaller than anything else and has an integrated Bluetooth radio; just what you need when you need an Internet of Motes of Dust.

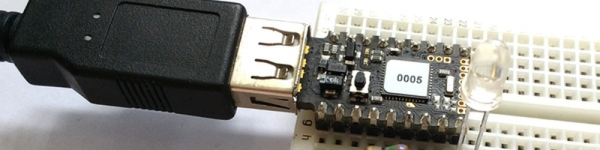

The Atmel BTLC1000 is a tiny SoC designed for wearables. The internals aren’t exceptional in and of themselves – it’s an ARM Cortex M0 running at 26 MHz. There’s a Bluetooth 4.1 radio inside this chip, and enough I/O, RAM, and ROM to connect to a few sensors and do a few interesting things. What makes this chip so exceptional is its size – a mere 2.262mm by 2.142mm. It’s a chip that can fit along the thickness of some PCBs.

To provide some perspective: the smallest ATtiny, the ‘tiny4/5/9/10 in an SOT23-6 package, is 2.90mm long. The smallest PICs are similarly sized, and both have a tiny amount of RAM and Flash space. The BTLC1000 is surprisingly capable, with 128kB each of RAM and ROM.

The future of wearable devices is smaller, faster and more capable devices, and with a tiny chip that can fit on the head of a pin, this is certainly an interesting chip for applications where performance can be traded for package size. If you’re ready to dive in with this chip the preliminary datasheets are now available.