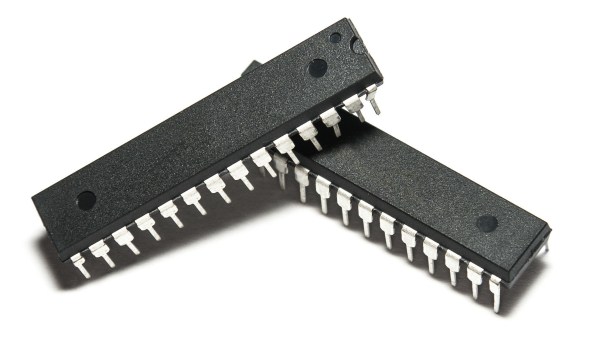

You might have caught Maya Posch’s article about the first open-source ASIC tools from Google and SkyWater Technology. It envisions increased access to make custom chips — Application Specific Integrated Circuits — designed using open-source tools, and made real through existing chip fabrication facilities. My first thought? How much does it cost to tape out? That is, how do I take the design on my screen and get actual parts in my hands? I asked Google’s Tim Ansel to explain some more about the project’s goals and how I was going to get my parts.

The goals are pretty straightforward. Tim and his collaborators would like to see hardware open up in the same way software has. The model where teams of people build on each other’s work either in direct collaboration or indirectly has led to many very powerful pieces of software. Tim’s had some success getting people interested in FPGA development and helped produce open tools for doing so. Custom ASICs are the next logical step.

Continue reading “Your Own Open Source ASIC: SkyWater-PDK Plans First 130 Nm Wafer In 2020”