Neon lights are that kind of nostalgic item that everybody seems to love. The neon lamp is a type of gas discharge lamp, they generate light when an electrical discharge travels through an ionized gas, or plasma. When the voltage between the electrodes exceeds certain threshold, the gas ionizes and begins conducting electricity. The basic process that generates light is the return of the ions to the ground energy state, with the emission of a photon of light. The light color depends on the emission spectra of the atoms in the gas, and also on the gas pressure, among other variables. Gas discharge lamps can be classified by the pressure of the gas:

- Low pressure: includes the neon lamp, fluorescent lamps and low pressure sodium lamps.

- High pressure: such as the metal halide, high pressure sodium and mercury vapor lamps.

Another classification comes from the heating method of the cathode:

- Hot cathode lamps: the electric arc between the electrodes is created via thermionic emission, where electrons are expelled from the electrodes because of the high temperature.

- Cold cathode lamps: In these, the electric arc results from the high voltage applied between the electrons, that ionizes the gas and conduction can take place.

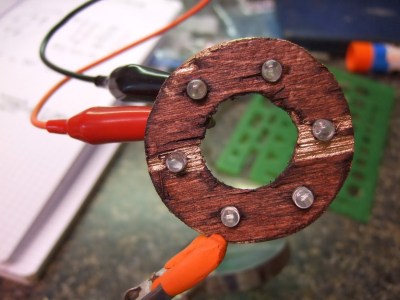

High intensity lamps are another type of gas discharge lamp where a high power arc is formed between tungsten electrodes. Power levels of several kilowatts can be easily produced this type of lamp. Of course we can’t forget to mention nixie tubes, which are a type of cold cathode neon lamp, popular for building retro clocks. Fortunately, they are now in production again.