When the only tool you’ve got is a hammer, every problem starts to look like a nail. Similarly, while a 3D printer is a fantastic tool to have, it can make you think it’s possible to build all the things with printed parts. Knowing when to print ’em and when to machine ’em is important, a lesson that [Diffraction Limited] has taken to heart with this semi-printed silent air compressor.

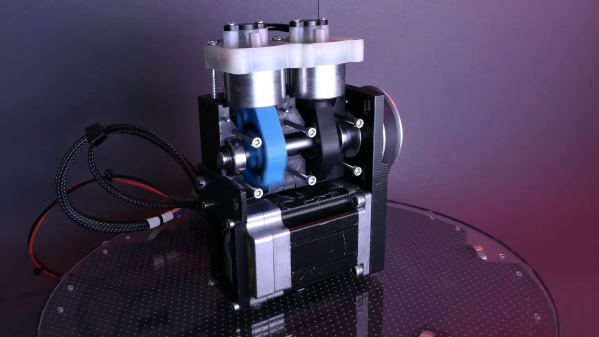

The key to this compressor’s quiet operation is a combination of its small overall size. its relatively low output, and its strategic use of plastic components, which tend to dampen vibrations. The body of the compressor and the piston arms are the largest 3D-printed parts; the design calls for keeping printed parts in compression for longer life, while the parts of the load path in tension travel through fasteners and other non-printed parts. The piston design is interesting — rather than being attached to connecting rods via wrist pins, the machined Delrin pistons are solidly attached to the piston arms. This means they have to swivel within the cylinders, which are made from short pieces of metal tubing, with piston seals designed to move up and down in grooves on the pistons to allow air to move past them. The valve bodies atop each cylinder are salvaged from another compressor.

When powered by a NEMA23-frame BLDC motor via a belt drive, the compressor is remarkably quiet; not quite silent perhaps, but still impressively smooth, and capable of 150 PSI at low speeds. And as a bonus, the split crankcase makes it easy to open up and service, or just show off how it works. We’ve seen a variety of 3D-printed compressors, from screw-type to Wankel, but this one really takes the prize for fit and finish. Continue reading “Small, Quiet Air Compressor Puts 3D-Printed Parts To Best Use”